Access to Health Care in NYC: Borough Inequality + the Pandemic Effect

Health Care is the city’s largest industry, but when it comes to access, not all boroughs are created equal. And job losses from COVID-19 have only amplified this inequality. What can be done?

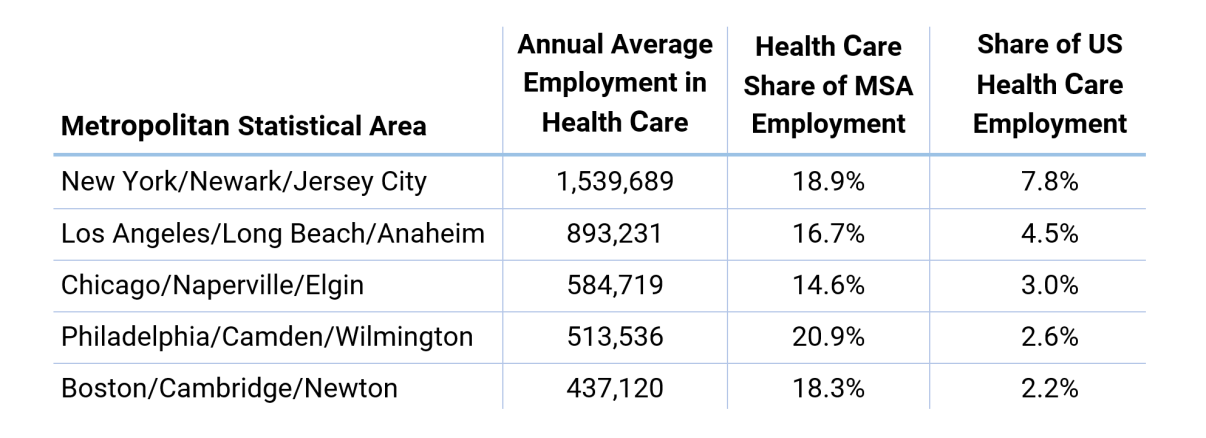

The Health Care and Social Assistance industry is by far the largest employer in the US, accounting for nearly 16% of total private employment and boasting over 19.7 million employees, 4 million more than the next closest sector, Retail Trade. The same is true of New York City—where Health Care’s 740,000 employees account for nearly 20% of total private employment—and of the surrounding Metropolitan Area.1

Generally, health practitioners are among the better-paid workers in NYC. The average annual wage for Health Care Practitioners and Technical Occupations (not including support functions) is just over $100,000, which is far above the average for all industries. But wages in Health Care depend heavily on occupation. Doctors average $165,000 per year, but nurses, technicians, and support occupations earn far less.2 Registered nurses, the largest Healthcare Practitioner occupation by employment in NYC —numbering over 72,000—earn $98,440 annually on average. Licensed practical nurses (LPNs), which total nearly 14,000, earn about $56,600 per year.

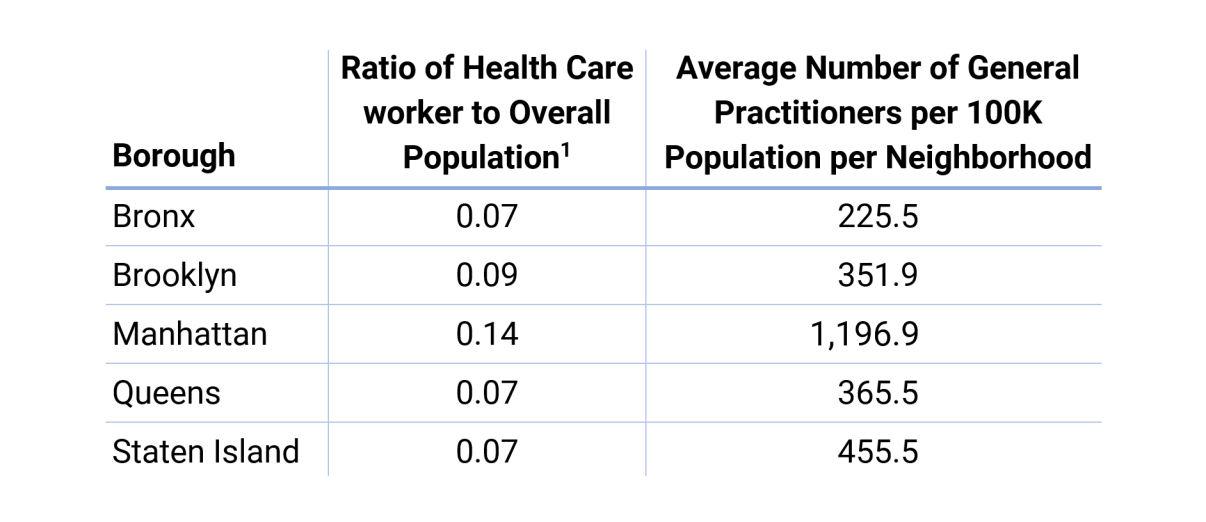

Borough Inequality

Despite the size of the Health Care industry in the NYC, jobs and facilities aren’t evenly distributed among the five boroughs. Manhattan has double the number of Health Care workers for every 100 inhabitants than the Bronx, Queens, and Staten Island. Moreover, the uneven location of certain Health Care facilities has created effective health care deserts in various NYC neighborhoods, where access to qualified personnel can be difficult. The divide is further evident in the disparities of general practitioners.3

Furthermore, averages in boroughs other than Manhattan are skewed upward by the concentration of general practitioners in a few neighborhoods, to the detriment of some others.

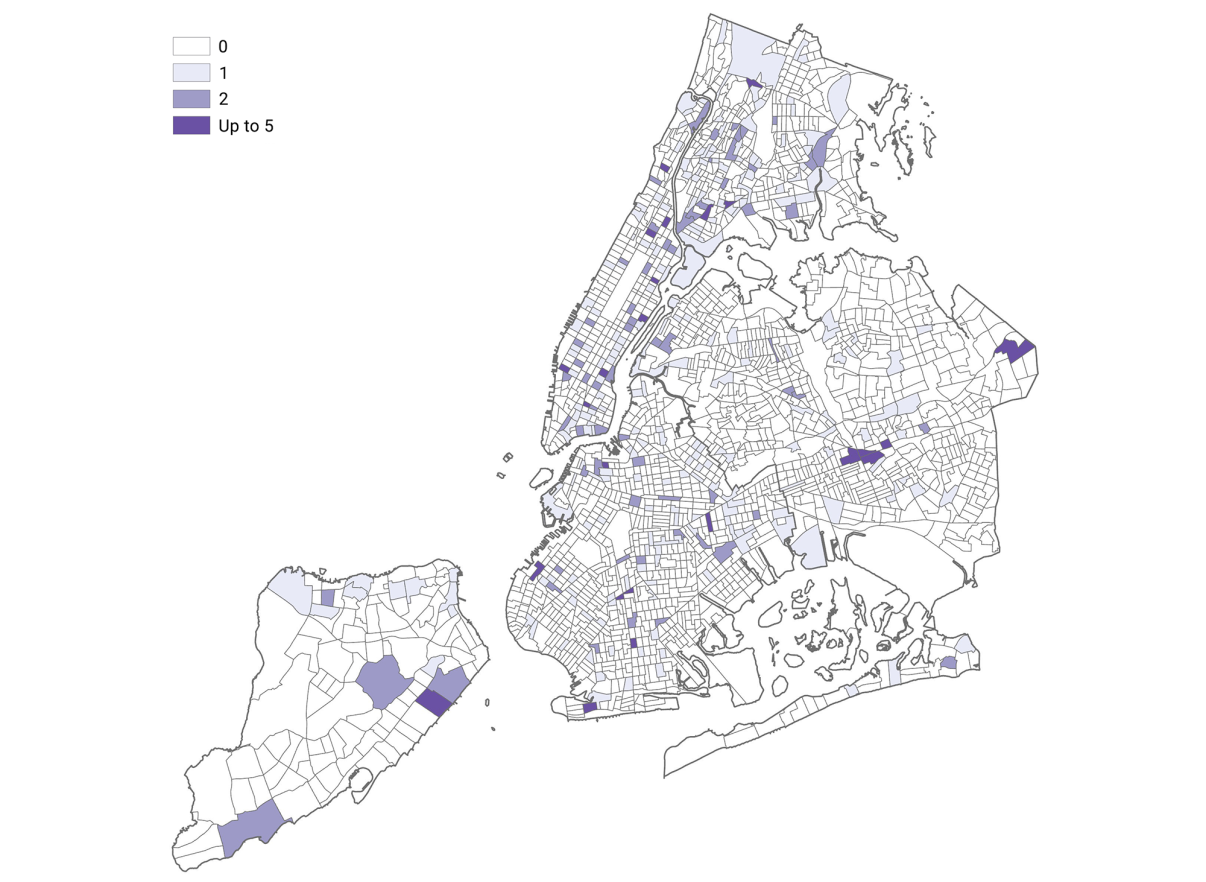

According to New York State Department of Health data, there are over 1,300 Health Care-providing facilities in NYC. However, many of these are specialized centers; only about 450 offer some form of primary care, with 52% of these in Manhattan and Brooklyn. Meanwhile, many parts of Queens and the Bronx are underserved by primary care facilities. While certain disparities are expected given population differences among areas, the absence of facilities in neighborhoods lacking proper access to affordable transit is problematic.5

Figure 1. Primary/Family Care Facilities in New York City6

2020, 438 Primary/Family Care Facilities in New York City. Source: NYS State Healthcare Data, NYCEDC, MGIS 02/2020.

Hit Hard by COVID-19

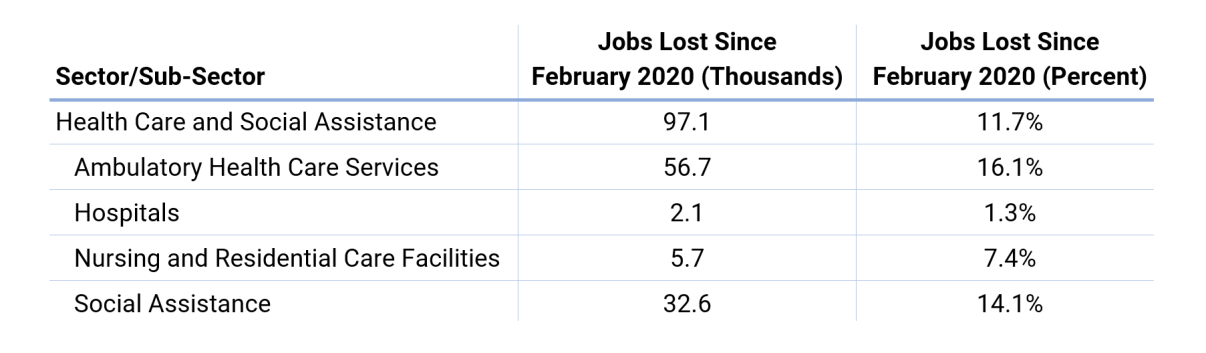

Health Care has been put under enormous stress by COVID-19. Between February and April 2020, the sector in NYC lost nearly 100,000 jobs—roughly 11.7% of its workforce—and it is projected to further diminish in 2020.7

Further, the sector has been under intense financial pressure nationwide—revenue is down and many elective procedures are being cancelled due to COVID-19.8 Ambulatory care, doctor’s offices, and dentist’s offices have driven losses nationwide. As the economy progressively reopens, demand for these services is likely to return and provide a relative rebound in employment, but it will take time for the sector to return to its previous levels of employment.

Path to Access: In-Home Care and Outpatient Visits

Currently, there are several ways to provide access to populations in underserved communities. In-home care and mobile/outpatient care allow those with the least mobility—generally older people—to receive quality care. But even these paths to access have roadblocks. An increase in NYC residents aged 65 and older in the coming decades will likely create higher demand for and, as a result, shortages in quality outpatient care in a city where access to this care is already unevenly distributed.9 (In addition, the current pandemic renders it difficult to emphasize outpatient care in the short term.) Further, job losses in Home Health Care, which would mean less basic care possible at home, may drive even more people to seek outpatient care. Given these factors, expanding the supply of workers able to perform routine outpatient procedures is a potential solution, especially as the economy recovers.

There are nearly 14,000 LPN employed in NYC and national projections indicate that it will be one of the fastest-growing occupations in the US.10 Like RNs, LPNs undertake countless duties in a variety of settings and are trained to perform routine procedures such as taking vitals, administering injections, and monitoring catheters, among others. Although some work in hospitals, 2017 survey data indicate that most LPNs are employed in nursing home and extended care facilities.11

Expanding the supply of workers able to perform routine outpatient procedures is a potential solution, especially as the economy recovers.

The cost of LPN programs—averaging between $10,000 and $15,000 in tuition alone12—could be a deterrent for some applicants, but given the occupation’s lower regulatory barriers to entry, LPNs currently offer the best prospect to alleviate the shortage of nurses and outpatient care.

Whether through increasing the LPN workforce or some other solution, the unequal access to primary Health Care throughout NYC will need to be addressed, especially as the city’s proportion of elderly residents increases in the future.

Learn more about NYCEDC’s Economic Research & Policy group at edc.nyc/Insights and contact the team at [email protected].

SOURCES

1. Based on 2018 annual averages from US BLS Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages.

2. Based on data from NYS Department of Labor Occupational Employment Statistics for New York City.

3. General practitioners defined as Physicians, Physician Assistants, and Nurse Practitioners as classified by the US Census Bureau.

4. Population is based on 2018 estimates from the US Census Bureau.

5. Sarah M. Kaufman, Mitchell L. Moss, Jorge Hernandez, and Justin Tyndall, Mobility, Economic Opportunity and New York City Neighborhoods, NYU Rudin Center for Transportation (November 2015).

6. Data does not include facilities providing specialized care such as dialysis centers or Planned Parenthood facilities.

7. Based on data from NYS Department of Labor and NYCEDC projections based on REMI/RSQE; projections are subject to change in future iterations.

8. Health-Care Workers See Steep Job Losses From Coronavirus - Wall Street Journal

9. New York City Population Projections by Age/Sex & Borough, 2010-2040, New York City Department of City Planning (December 2013)

10. Based on projections from US BLS.

11. Data from the 2017 National Nursing Workforce Study administered by the National Council of State Boards of Nursing.

12. Based on estimates from practicalnursing.org.