In 2022, when New York City voters approved a preamble to the New York City Charter declaring that the City “endeavor[s] to ensure that every person [has]…[s]afe, secure, and affordable housing,” they made explicit a goal that has been at the core of the Charter’s structure since New York City was consolidated in 1898.1 Over 125 years, the question of how to house New Yorkers—and how to plan for the city’s growth—has driven some of the most consequential changes to the City Charter. As powers have shifted between State and City, and as New York’s economy and society have transformed, policymakers have continuously sought to strike the right balance between citywide and local perspectives in questions of land use, planning, and housing. Each successive Charter has built on the ones that came before it, always adding new ideas to respond to evolving realities and to correct flaws in the Charter that revealed themselves over time. As today’s Commission considers potential changes to the City’s housing and land use processes, it may consider how prior revisions to the Charter—and their consequences—can inform future reforms. If changes are made, they will be a part of a long history of evolution in the City’s foundational document.

Land Use in Post-Revolution New York

Before New York City’s consolidation in 1898, some of the most important land use issues were governed by New York State, not the cities and towns that now make up the five boroughs. New York City’s street grid, put in place by the Commissioners’ Plan of 1811, was created by the State, in part because New York City’s Common Council could not come to an agreement about how to lay out the city and see to its growth.2 Similarly, some of the first major laws to regulate housing were state laws: a ban on wood construction south of 32nd street in 1849,3 the Tenement House Acts in 18674 and 1879,5 and even the introduction of fire escapes in 1860.6 In this period, New York City did little to regulate housing and land use in the ways we think of today. Instead, development followed the elevated train lines (each individually chartered by the State) into new neighborhoods and across the Brooklyn Bridge (permitted by State law) into Brooklyn, with City government playing a limited role in the city’s growth.

The Consolidated City Charter and Land Use

By 1901, soon after New York City’s 1898 consolidation, the Charter included many of the same officials we have today, including a Mayor, Borough Presidents, and a Comptroller, who—along with a City Council President7—constituted the Board of Estimate.8 However, City government’s power over land use was still relatively limited.

One of the few ways that government could directly influence development was in determining the layout of streets, a power left to the Board of Alderman,9 a legislative body with members elected from specific districts. Laying out and changing streets not only determined new development patterns but also influenced the location and construction of bridges—particularly the newly planned East River bridges (Williamsburg, Manhattan, and Queensboro) that would link Manhattan and the outer boroughs.10

Consumed by concerns about the impact of changes on individual districts, the Board of Alderman proved a difficult place to secure changes to the city map. Particularly concerning to then-Mayor Seth Low, the Board of Alderman resisted changes needed to construct the East River bridges, which would require the displacement of many longtime residents. In response, in 1903 Mayor Low successfully asked the State Legislature to alter the New York City Charter and transfer this critical power to the Board of Estimate.11 In Mayor Low’s view, the laying out of streets and bridges “must be carried out from the general point of view. If it must wait until it can also command local approval—such as the Board of Alderman represents—years are likely to pass before anything can be done, and during all those years the city will suffer.”12 To Mayor Low, progress was being limited by a parochial, legislative body in the face of citywide needs—a dichotomy that policymakers would confront many times over the next century. The changes made in 1903 were the first in a long history of Charter revisions aiming to improve upon perceived defects in the structure of land use review in New York City.

The Board of Estimate and Zoning

In 1914, the Charter was changed again to give the Board of Estimate the ability to regulate “Height and Open Spaces” and the “Location of Industries and Buildings”—namely, the power to legislate zoning.13 Two years later, the Board of Estimate enacted the country’s first comprehensive zoning code, and importantly, left itself the power to amend it.

The administration of the zoning code quickly became intensely political and frequently hyper-local. Local political machines would weigh in on zoning requests and make their preferences clear to the respective borough president. Borough presidents, as members of the Board of Estimate, developed “borough courtesy,” whereby a land use decision in one borough would see all of the borough presidents on the Board of Estimate vote in lockstep with the borough president whose borough was being impacted.14 Frequently, these powers were used to protect entrenched political interests in specific areas, such as preserving certain neighborhoods from the “encroachment” of apartment houses.15

The Board of Estimate was not, however, the only way that land use rules changed in New York City during this period. Changes to land use were also made by the Board of Standards and Appeals, which was created to grant “relief” to hardships imposed by the zoning code.

These variances were intended to be administered by an impartial board appointed by the mayor, but the Board of Standards and Appeals—especially in the 1920s—began to take on an overtly corrupt flavor. In 1931, Judge Samuel Seabury’s in-depth investigation into corruption in New York City found the Board of Standards and Appeals was the site of significant mischief. In one case, the politically connected former chief veterinarian for the Fire Department made over one million dollars by representing clients before the Board of Standards and Appeals.16 Seabury’s report would result in the resignation of Mayor Jimmy Walker and lead to Seabury’s appointment to a State-enacted Charter Revision Commission. In 1934, Seabury would himself resign after the initial proposed Charter reforms were scrapped, leading to the elimination of the Commission. A year later, Mayor LaGuardia would appoint a new Charter Revision Commission, led by former United States Solicitor General Thomas Thacher, which would enact sweeping changes to the New York City Charter.17

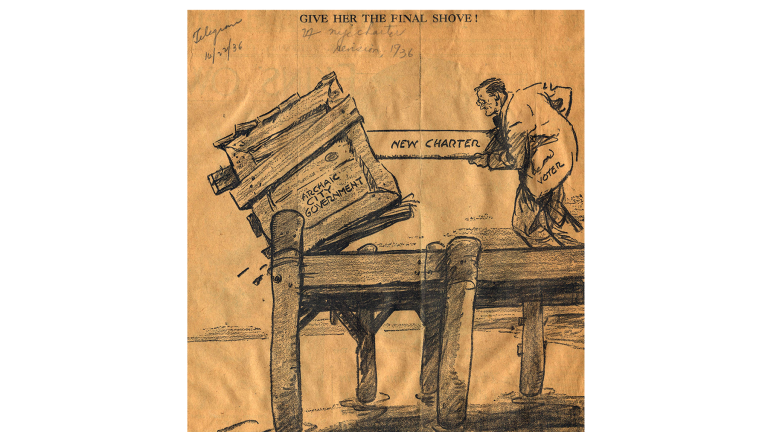

The 1936 Charter

The Thacher Commission made two monumental changes to land use in New York City: the requirement of a master plan and the creation of the City Planning Commission. The desire for a new system of regulations for land use was not only a response to prevalent corruption under the old system, but also a genuine desire for better planning. Even before the Thacher Commission was created, there was a growing acknowledgement that the zoning code did not meet the city’s needs or realities: A report from this era pointedly noted that 4 million people, well over half of all New York City residents, lived in areas not zoned for residential use.18 Under the Thacher Charter, a new independent body, the City Planning Commission (CPC), would be responsible for both preparing a master plan for New York City and for the ongoing administration of the zoning code.

In 1936, voters also approved a significant reduction in the power of the Board of Estimate over land use. Not only would the Board no longer be able to initiate zoning changes, but it would now need a super majority (75%) in order to overrule the City Planning Commission.21 Yet despite the idealized independence of the City Planning Commission and its broad mandate, the CPC struggled to approve a master plan or make significant changes to the zoning resolution. This period was described by one historian as the “Years of Frustration,” with the City Planning Commission “consistently beaten on its zoning proposals, completely ineffectual in its other Charter-mandated duties” and in a “changing city…seem[ingly] unable to control its own activities, much less impose a guiding hand on the physical development of the city.”22 The absence of strong support in civil society, as well as opposition to changes from entrenched real estate interests, resulted in the borough-based Board of Estimate consistently declining to support any master plan. And so the process of piecemeal amendments to the zoning code continued, with hundreds of changes made prior to a full-scale overhaul of the zoning code in 1960.

The absence of a larger overhaul between 1938 and 1960 was not for lack of trying, or recognition of the need for change. The first master plan under the new Charter was attempted in 1940 by Rexford Tugwell, a prominent planner and former member of President Roosevelt’s New Deal “Brain Trust.” The plan sought to greatly increase the amount of parkland in New York City but struggled to gain support and was attacked relentlessly by Robert Moses, who was skeptical of the plan’s 50-year time frame.23 Moses would join the CPC upon Tugwell’s resignation in 1942, and would himself successfully enact a significant downzoning in 1944, although within the existing structure of the 1916 ordinance. In 1948, CPC Chair Robert F. Wagner Jr. would begin the push for a new comprehensive plan, which languished until the mid-1950s. The origins of the 1961 zoning code—a zoning code that is largely still in effect—date to 1955, when Wagner (now mayor), appointed James Felt as Chair of the CPC. It would be Felt who would successfully shepherd a fundamental re-write of the zoning code to approval in 1960.24

The new zoning resolution went into effect in 1961 and housing that had been grandfathered in under the prior zoning continued to be built into the middle of the 1960s. But following passage of the 1961 zoning code, the city saw a significant drop in housing production beginning in the mid-1960s from which it has never recovered.

In 1969, the Lindsay administration produced one final attempt at a master plan, the “Plan for New York City.”26 A sweeping five-volume plan, it touched everything from jobs, to transit, education, housing, industrial growth, open space, and more. But the plan was never adopted and “was viewed as a costly failure,” leading to the removal of “master plan” requirements from the Charter in 1975.27 The fundamental structure of the 1961 zoning code has remained in place ever since.

The 1961 Charter

The same year that New York City’s amended zoning code went into effect, New Yorkers once again voted to amend the Charter’s land use procedures. These changes were relatively minor: the chairman of the City Planning Commission (and consequent head of the Department of City Planning) now served at the pleasure of the mayor, and the Charter instituted a new system of Community Planning Boards, based on Community Planning Councils that already existed in Manhattan. These boards were to advise the borough presidents with respect to the “development or welfare” of a district and to “advise the city planning commission…[with] respect to any matter…relating to its district.”28 The Charter also removed the Borough Presidents’ authority over streets, highways, and sewers, but left the offices, including each Boroughs’ Topographic Office, otherwise intact.29 (For more on the decentralized administration of the City’s mapping and its impacts see the Staff’s Preliminary Report.) The Borough Presidents’ positions on the Board of Estimate, which retained critical land use powers, and their power to appoint members of the Community Planning Councils, ensured that they would play a continued role in housing and planning.

The 1975 Charter

In 1972, New York State created a Charter Revision Commission, citing the need for “structural reform of city government…to encourage genuine citizen participation in local city government [and] ensure that local city government is responsive to the needs of its citizens.”30 The city had transformed since the 1936 Thacher Commission, the last major restructuring of City government: out of the Great Depression, through a World War and a booming post-War economy, into a period of accelerating suburbanization. As it entered the 1970s, the city confronted new racial tensions, political tumult, a weakening economy, and a ballooning fiscal crisis. In their final report, the Commission summed up the mood of the time: “the years since 1961 have telescoped time and produced the equivalent of decade of turbulent and extraordinary change. The City has had massive demographic shifts...Frustration, hostility, and apathy—all at the same time—have marked the mood of the City’s body politic.”31 If 1936’s Charter reforms were intended to modernize the Charter, reduce corruption, and improve planning in a recovering city, 1975’s changes were an effort to save a city that seemed on the brink of collapse.

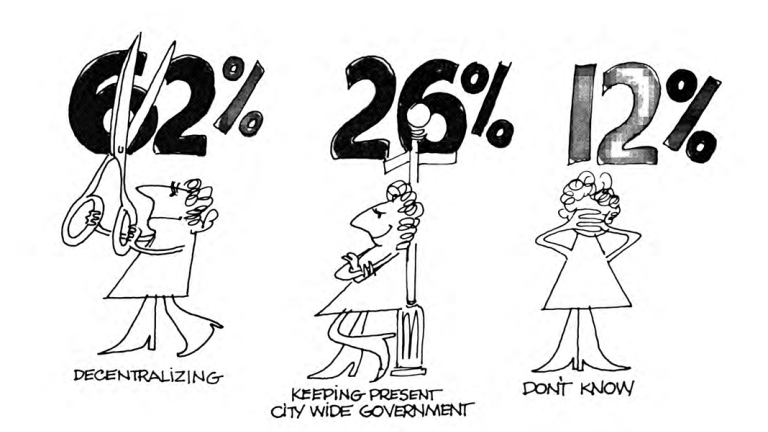

From the early days of that Commission, it was clear that decentralization—the desire to make government closer to the people, rather than highly centralized—would be a key focus. In their introductory report, the Commission made this clear by citing survey results showing that 62% of New Yorkers sought a more decentralized government, and the Commission expressed its view that “more decisions on local government activities should be made locally” though they had “not yet agreed on a specific plan for decentralizing City government.”33

Support for decentralization strengthened as a result of several high-profile land use fights in the 1970s that pitted local community members against decisions from City Hall. One particularly salient case was the vitriolic opposition to a new public housing development in Forest Hills, Queens. Originally proposed in 1966 as low-income housing in neighboring Corona, by 1971 it was clear that the project would be moved to Forest Hills. Community opposition was so fierce that the project was eventually halved in size and assurances were given that the new housing would primarily go to seniors and residents who already lived in the area.34 That housing was built at all in Forest Hills is a credit to Mario Cuomo, then a private lawyer appointed as a mediator by Mayor Lindsay, who ably navigated competing tensions to find a compromise that would satisfy the local community. But even as he charted a public solution, Cuomo was privately skeptical of his charge. Writing in his diary in June 1972, just a month after being asked to take the role by the mayor, Cuomo recorded:

[T]he idea of absolute community control, while superficially appealing, cannot work in this city. Obviously, were each community, like Forest Hills, to have the last word on public projects within its boundaries, public projects and, therefore, city life would be almost totally stultified…[T]otal decentralization of governmental power in this city is neither wise nor practicable.35

Despite Cuomo’s reservations, he successfully negotiated an agreement few thought possible. And the same week that Cuomo’s “Forest Hills Compromise” passed the City Planning Commission, Governor Rockefeller announced the members of the 1972 Charter Revision Commission.36 As the Charter Revision Commission began its work, it took a particular interest in community boards, which had played a large role in the pushback against projects like Forest Hills. Ultimately, the Commission would attend meetings in 59 of the then-62 boards.37 These boards had grown in prominence following the Forest Hills controversy, with many politicians actively linking that conflict to an increasing demand to serve on the boards.38 Thus, as the Commission sought to elevate community views in a new, decentralized governance regime, community boards took on an increasingly important role.

Kenneth Clark, who, with his wife Mamie Phipps, had conducted research critical to the Supreme Court’s ruling in Brown v. Board of Education, provided “some of the most moving testimony” to the 1975 Commission interpreted as “very valuable caution against rushing into new areas of decentralization in government.”40

As the fiscal crisis became increasingly urgent to the Commission between its formation in 1972 and conclusion in 1975, the question of how much power to give community boards slipped further down their list of priorities. Ultimately, a minority of commissioners put forward a ballot measure that would have allowed community boards to be elected and have a binding decision-making role (though only if the mayor, Board of Estimate, and City Council agreed to delegate such powers, a perhaps unlikely outcome), and voters rejected that measure by a nearly 2 to 1 margin.41 By contrast, a measure creating community boards’ advisory role in ULURP was approved 54% to 46%.42

Early reports prepared for the 1975 Commission predicted that even in an advisory role “Community Board opposition to a project will, as a practical matter, spell its defeat.”43 Those concerns proved well-founded. In 1987, a mayoral official suggested that the City Planning Commission and the Board of Estimate “follow[ed] the advice of the [community] boards in well over 80 percent of cases” and that the remaining proposals were meaningfully shaped by community board recommendations.44 Nevertheless, many large-scale projects moved ahead, aided by the willingness of developers to make concessions to secure political support and the broader city-wide and less parochial views of both the City Planning Commission and the Board of Estimate.

The 1975 creation of ULURP was not only intended to empower local communities. It also was designed to promote transparency and certainty in a land use process that was opaque and indeterminate. As Staten Island Borough President Ralph Lamberti explained, one goal of ULURP “was not to give more time for review, it was to shorten it…Because what was happening was, the building industry, developers came forward and said we submit applications [but] we can’t get an answer.”45To this day, ULURP continues to play this critical role: clarifying and standardizing the process for land use changes, while providing meaningful opportunities for public input.

Mayor Beame and Cultural Affairs Commissioner Martin Segal, Feb. 8, 1977.

The 1975 Charter also changed the makeup and powers of the City Planning Commission. It would no longer be responsible for a master plan—an admission that this responsibility, created in 1936, had faced intractable obstacles, with no plan ever adopted. The Commission would also no longer be made up of solely mayoral appointees. Instead, it would have representation from all five boroughs and have new “flexible requirements,” for developing both “City-wide and local plans.”46

The 1989 Charter

The impetus for the 1989 Charter Revision Commission was not land use, but instead democracy: the Supreme Court of the United States had declared the Board of Estimate unconstitutional and New York City had to reconstitute its legislative branch.47

The 1989 Charter Commission, led by Frederick A.O. Schwarz Jr., placed the City Council at the end of ULURP as part of a broader restructuring of a post-Board of Estimate City government. The newly empowered City Council became a districted legislative body with 51 members, each with a single vote. And the Charter Commission granted the Council ultimate review over the full range of land-use actions, big and small—from zoning map and text changes to project-specific special permits and dispositions.

Even at the time, many feared that giving the City Council final say over all land use matters would give rise to a practice of member deference, under which the entire legislative body would defer to the local member in votes on land use matters. This in turn would stymie important land use changes, as then-Mayor Koch warned the Commission:

I fear that your proposal will give legislative legitimacy to the NIMBY reaction that now threatens to block any socially responsible land use policy. The legislative tradition of comity and deference, which grants one legislator, in essence, the power to determine the collective vote on matters affecting his or her district, means that any time a member of the City Council does not like a land use decision in his or her district, that member will have no difficulty mustering the required votes to take jurisdiction and vote it down. This is a sobering thought. We would run the risk of land use paralysis.48

The New York Times Editorial Board expressed similar concerns, warning that the Commission’s proposal “makes an expanded and inevitably more parochial Council the final arbiter on most land-use issues.”49 Eric Lane, the Commission’s Executive Director, likewise warned that “If you require council approval of [a zoning change] ... the Council member in whose district it would be would... basically be able to stop the project. [The legislature would] just give deference to the member whose district it is in.”50

In response to concerns about “land use paralysis,” the Commission had initially sought to give the newly empowered Council a role only in broad citywide land use initiatives but no role in “project-specific” land use decisions.51 Early proposals before the commission would have dramatically reshaped the ULURP process, splitting projects into those of “general zoning” and “site specific zoning,” with a legislative body only involved in the former. However, over time, Chair Schwarz took the view, “after lengthy talks with lots of people, that there is no such bright line” between the two.52 As such the Commission moved forward with a plan to maintain a unified ULURP under the CPC.

The commission did still try to limit the types of activity subject to Council review under ULURP, to ensure that the Council was able to focus on “issues of broad concern and budget matters.”53 Ultimately, however, some members of the Commission felt that particularly controversial projects should receive political oversight from a legislative body, and numerous groups testifying before the Commission agreed.54 Both special permits and property dispositions were made subject to council review. It was felt that the large-scale disposition of City property (as was common during the period) was “the functional equivalent of a zoning change” for lower-income communities and thus should be subject to council review.55 Similarly, concerns about the potential importance of special permits led to Council review for those items.56

The final Charter proposal reached a compromise, including both a “Fair Share” framework that would help evenly distribute undesirable municipal necessities (such as incinerators and garages) and the ability for the City Council to review any action under ULURP, by subjecting almost all actions to a Council call-up, with the assumption that it would be rarely used. The goal of Council review should only be to “right egregious wrongs,” Executive Director Lane said in 1989, not allow a single Council member to “exercise a particular community’s distaste for a particular project” and “stop things from going forward in the city.”57 Reflecting on that compromise in an appearance before the City Council in 2024, Lane testified that he still regrets the 1989 Commission’s failure to include a “mechanism that would stop ... individual members” from vetoing land use projects.58

Post-1989

The 1989 changes did not immediately lead to “land use paralysis.,” though they did lead to a pronounced drop in ULURP applications, and in particular residential applications.59 The practice of “member deference,” in which the City Council as a body defers to the preference of the individual local member, would not solidify until the 21st century. (For more on this practice and its impacts, see the Preliminary Staff Report’s housing chapter.)

Instead, throughout the 1990s, the newly empowered City Council largely maintained a citywide perspective on matters of citywide importance. As 1990s City Council Speaker Peter Vallone explained in his 2005 memoir, “the Council’s record on land use...proved its capacity for favoring the city’s overall interests rather than the parochial interests of local neighborhoods....[despite] real fears from the Charter Revision Commission that the council might adopt a small-minded attitude against development.”60 Vallone noted that throughout the 1990s, largescale projects were approved over the objections of local councilmembers, including a condominium project on City Island and the large Riverside South complex on the Upper West Side. Other big zoning changes, such as significant updates to the Special Theater Subdistrict were also approved over the objections of local councilmembers.61 As the New York Times put it: “There are many more participants than before [in the land use process]. Yet the Council is much more firmly under the control of one person,” Council Speaker Vallone.62

Around the turn of the millennium, the practice began to change, with member deference overruled fewer and fewer times. Some practitioners attribute this change to the introduction of Council term limits, to City Council rules reforms that may have weakened the Speaker’s ability to influence individual members, and to a change in general political attitudes toward new housing, as development pressures accelerated in the 2000s.63

Whatever the reason, after 2000, there are only a few major examples of members being overruled—typically non-residential projects like a police academy in Queens whose citywide importance were more legible. At the time of writing, the last residential project to be approved through ULURP over the objection of a local member was in 2009—16 years ago.64

Examples of Member Deference Being Over-Ruled in ULURP Actions Since 200065

| Year | ULURP # | Description | Category |

| 2021 | 210351ZMM | New York Blood Center | Commercial |

| 2009 | 090403 PSQ | New York Police Academy | City Project |

| 2009 | 090184 ZSK | Dock Street Development | Residential / Mixed-use |

| 2009 | 090415 HUK | Broadway Triangle Rezoning | Residential / Mixed-use |

| 2009 | 090470 PPQ | College Point Corporate Park | Commercial |

| 2007 | 070315 (A) ZRQ | Jamaica Rezoning | Residential / Mixed-use |

| 2007 | 20095400 SCQ | Maspeth High School | City Project |

| 2004 | 040217 ZSK | Watchtower Development | Residential / Mixed-use |

| 2004 | 040445 ZSM | Harlem Park Hotel | Commercial |

| 2003 | 030158 PSK | NYCEM Headquarters | City Project |

| 2002 | 010602 ZSM | Special Permit for a Manhattan Parking Garage (Upper West Side) | Other |

| 2001 | M 820995 | Hotel near La Guardia Airport | Commercial |

Today, despite member deference not being in the Charter at all, it is firmly entrenched. The most critical phase of public review of a land use proposal is now the effort to win the local member’s support. And because some councilmembers are categorically opposed to new housing, some districts see no proposals for new housing at all. As Borough President Antonio Reynoso put it, there are districts where the councilmember “shut[s] down every single project before it even starts,” the outcome so many had feared in 1989.66

Should the Commission propose changes to the Charter’s land use process, and should voters approve those changes at the ballot box, these reforms would represent just the latest change to a document that has continuously evolved over the decades to respond to the needs of a changing city.

Header Image: Mayor Seth Low (center) hammers in a spike for the IRT subway, ca. 1902-04.

References

1. Charter Preamble.

2. Hilary Ballon, ed., The Greatest Grid: The Master Plan of Manhattan 1811-2011 (Columbia University Press, 2012), at 29. Balloon also notes that the Common Council was unable to make any plan permanent and not subject to the whims of a future Common Council.

3. 1849 N.Y. Laws ch. 84.

4. 1867 N.Y. Laws ch. 908.

5. 1879 N.Y. Laws ch. 504.

6. 1860 N.Y. Laws ch. 470.

7. The City Council President’s role still exists today in the form of the Public Advocate, after the City Council renamed the position in 1993. See Local Law No. 19 of 1993.

8. In 1900, a coalition of groups (Republicans and outer borough Democrats) unhappy with Manhattan-based Tammany Hall’s control over New York City governance convinced Governor Theodore Roosevelt to form a Charter Revision Commission that would remove mayoral control of the Board of Estimate by eliminating the Corporate Counsel and president of the Department of Taxes (mayoral appointees) from their positions on the Board of Estimate and replacing them with the Borough Presidents, a system that lasted until 1989. See Joseph P. Viteritti, “The Tradition of Municipal Reform: Charter Revision in Historical Context,” (1989) Proceedings of the Academy of Political Science, Vol. 37, No. 3, at 22-23.

9. Between 1898 and 1901, New York City briefly flirted with a bicameral legislature, but returned to unicameralism in 1901. In 1898 the Charter read that “[t]he legislative power of the City of New York shall be vested in two houses,” but in 1901 it was to be “vested in one house to be known and styled as ‘the board of aldermen.’” See Charter § 17 (1898); Charter § 17 (1901).

10. The influence that a street plan could have on development was demonstrated by Borough President Louis F. Haffen. Known as the “Father of the Bronx,” in 1903 Haffen ensured that parts of the Bronx would be laid out as a grid, promoting dense housing development, rather than a series of winding streets, which would have been conducive only to single family homes. See Gregory F. Gilmartin, Shaping the City (Clarkson Potter, 1994), at 116.

11. The State legislature enacted the changes Mayor Low sought and amended Section 442 of the Charter to read: “The board of estimate and apportionment is authorized and empowered, whenever and as often as it may deem it for the public interest so to do, to change the map or plan of the city of New York, so as to lay out new streets, parks, bridges, tunnels and approaches to bridges and tunnels and parks.” 1903 N.Y. Laws ch. 409.

12. “Changes in City Map” New York Times, Page 3 May 2, 1903. Seth Low’s full statement is as follows: “In the near future great streets will have to be cut through densely populated sections, in both Manhattan and Brooklyn, in order to provide suitable approaches to the East River bridges now building, and generally to improve circulation in various parts of the city. Work like this, if done at all, must be carried out from the general point of view. If it must wait until it can also command local approval—such as the Board of Aldermen represents—years are likely to pass before anything can be done, and during all these years the city will suffer, while it may easily lose its opportunity altogether. Inasmuch as, under this bill, the individual approval of the Mayor is necessary, as it was under the Consolidation act, the danger of rash and inconsiderate action is not very great, but, whatever it is, I think the city had better accept this risk than the probability of practical inaction if the charter were to remain unchanged.”

13. 1914 N.Y. Laws ch. 470.

14. Stanislaw J. Makielski, Jr. The Politics of Zoning, (Columbia University Press, 1966), at 42-43.

15. Rather than zone for “single-family,” the initial 1916 zoning code sought to preserve single-family neighborhoods via extensive setback and lot coverage requirements. However, apartment buildings could still be built with large enough assemblages leading to even tighter restrictions with the introduction of zoning district “F” in 1922. In 1938, district “G” was created exclusively for “occupancy by a single family.” See Lee E. Cooper, “Fieldston Becomes First Area in City Zoned Strictly for One-Family Houses,” New York Times, Nov. 16, 1938; City Planning Commission, Zoning Resolution, Department of City Planning, 1960, at 82.

16. Seymour Toll, Zoned American (Grossman Publishers, 1969), at 208-209.

17. “New Charter Body Sworn By Mayor,” New York Times, Jan 23, 1935.

18. T.T. McCrosky, Zoning for the City of New York, Works Progress Administration, Aug. 1930, at 6-7.

19. 1936 Charter Revision Commission, “Report of the New York City Charter Revision Commission,” (Aug. 1936), at 10-11.

20. Id.

21. Charter § 200 (1938). The Charter adopted by voters in 1936 went into effect in 1938.

22. Makielski, The Politics of Zoning, at 83.

23. Jason M. Barr, “The Birth and Growth of Modern Zoning (Part III): Far and Wide,” Building the Skyline, Makielski, The Politics of Zoning, at 63.

24. Makielski, The Politics of Zoning, at 83.

Makielski “Years of Frustration” and “Rezoning New York” in The Politics of Zoning.

25. Voorhees Walker Smith & Smith, Zoning New York City, (New York, 1958) at vi-vii and at viii, 5.

26. New York City Planning Commission, “Plan for New York City, 1969: A Proposal” 1969.

27. Eric Kober, Senior Fellow Manhattan Institute, Follow-Up Testimony to the New York City Charter Revision Commission, (Mar. 27, 2025) (written testimony).

28. Charter § 84-b (1963). The Charter adopted by voters in 1961 went into effect in 1963.

29. According to City Administrator, Maxwell Lehman: “the Borough Presidents had their powers sharply cut under the new charter. The Charter Revision Commission had bitter debates as to whether the Borough Presidents should be eliminated altogether. A compromise was reached, mainly on the ground that local residents still want a center within the borough to which they can come with their complains. The Borough Offices lost control over highways, sewers and even bathhouses. But each Borough President was empowered to retain a topographical bureau, to recommend capital construction projects, be a member of the board which selects the sites for municipal structures, hold public hearings on matters of public interest, make recommendations to the Mayor and to other city officials in the interests of the people of his borough. They also select and exercise some supervision over the local district planning boards, which are designed to provide an effective voice for local neighborhoods.” Maxwell Lehman, “Power Distribution and Administration in New York City Government,” Pratt Planning Papers 3, no. 2 (November 1964), at 18. A minority of the 1975 Charter Revision Commission proposed undoing this change and returning the “responsibility for the design, construction, operations and maintenance of local streets and sewers” to Borough Presidents, but it was resoundingly defeated. See 1975 Charter Revision Commission, A More Efficient and Responsive Municipal Government: Final Report to the Legislature of the State Charter Revision Commission for New York City, 1977, at 2.

30. 1972 N.Y. Laws ch. 634.

31. 1975 Charter Revision Commission, “Preliminary Recommendations of the State Charter Revision Commission for New York City 1975,” (June 1975), at v.

32. Marshall Kaplan, Gans, and Kahn, Charter Reform of New York City’s Planning Function, Temporary State Charter Revision Commission for New York City, Oct., 1973, at 30.

33. 1975 Charter Revision Commission, “Revising the New York City Charter Introductory Report,” (n.d.), at 14.

34. Jacob Anbinder, “‘Power to the Neighborhoods!’: New York City Growth Politics, Neighborhood Liberalism, and the Origins of the Modern Housing Crisis,” Joint Center for Housing Studies, Mar. 11, 2024.

35. Mario Cuomo, Forest Hills Diary: The Crisis of Low-Income Housing (Vintage Books: 1975), at 79.

36. Francis X. Clines, “Planning Unit Approves Forest Hills Compromise,” New York Times, Oct. 5, 1972, at 51; William E. Farrell, “9 Chosen for Commission to Revise Charter for City,” New York Times, Oct. 4, 1972 at 1.

37. Anbinder, “Power to the Neighborhoods!.”

38. Jacob Anbinder, Postdoctoral Fellow at Cornell University, Brooklyn Hearing (February 11, 2025) (testimony) at 95.

39. 1975 Charter Revision Commission, Preliminary Recommendations of the State Charter Revision Commission for New York City 1975, (June 1975), at 113.

40. Frances X. Clines, “Clark, in Full About-Face, Calls for a Curb on Decentralization,” The New York Times, Nov. 30, 1972.

41. Question 9, “Shall community boards be elected and given responsibility to operate local parks and playgrounds, local recreation programs, neighborhood preservation programs, and local environmental inspection services as enumerated in amendments to the City Charter in Chapters 4, 51,52, 69, and 71?” failed 240,910 votes to 446,445 votes. See 1975 Charter Revision Commission, “A More Efficient and Responsive Municipal Government: Final Report to the Legislature of the State Charter Revision Commission for New York City,” 1977, at 2-3.

42. Question 6, “Shall new appointed community boards and borough boards with planning, budget, and service evaluation duties proposed as amendments to the City Charter in Chapters 2, 4, 51, 52, and 70 be adopted?” passed with 381,984 votes to 328,758 votes. See 1975 Charter Revision Commission, “A More Efficient and Responsive Municipal Government: Final Report to the Legislature of the State Charter Revision Commission for New York City,” 1977, at 2.

43. Kaplan et al., “Charter Reform of New York City’s Planning Function,” at 57.

44. Jennifer Stern, “Can Communities Shape Development,” City Limits, Mar. 1987, at 13.

45. Ralph Lamberti, Staten Island Borough President, Staten Island Charter Revision Commission Hearing (Apr. 22, 1987) (testimony) at 63-64 in Ronald H. Silverman, Land Governance and the New York City Charter, Sep. 1988.

46. 1975 Charter Revision Commission, “A More Efficient and Responsive Municipal Government: Final Report to the Legislature of the State Charter Revision Commission for New York City,” Mar., 1977, at 31.

47. Board of Estimate of City of New York, et al. v. Morris, et al., 489 U.S. 688 (1989).

48. Letter from Edward I. Koch, Mayor, City of New York, to Frederick A. 0. Schwarz, Jr., Chairman, 1989 New York City Charter Revision Commission (May 31, 1989) (on file with the New York Law School Law Review) in Frederick A.O. Schwarz Jr. and Eric Lane, The policy and politics of Charter making: the story of New York City‘s 1989 Charter, 42 N.Y.L. Sch. L. Rev. 723 (1998) at 859.

49. New York Times Editorial Board, “The Trees, and Tilt, in the Charter,” The New York Times, Jul. 30, 1989.

50. Eric Lane, Executive Director, Charter Revision Commission Hearing (May 10, 1989) (testimony) at 383-384.

51. Schwarz and Lane, The policy and politics of Charter making, at 860.

52. Frederick A.O. Schwarz Jr., Chairman, Charter Revision Commission Hearing (May 10, 1989) (testimony) at 259.

53. Id., at 386.

54. Schwarz and Lane, The policy and politics of Charter making, at 858-860.

55. Frederick A.O. Schwarz Jr., Chairman, Charter Revision Commission Hearing (June 15, 1989) (testimony) at 14. Ultimately, upon concern that this would make it challenging to transfer in rem foreclosures to tenant owners, Housing Development Fund Corporations (HDFCs) were exempted from automatic council review. See Charter § 197-d(b)2 and Nathan Leventhal, Commissioner, Charter Revision Commission Meeting (Aug. 1, 1989) at 138.

56. Judah Gribetz, Charter Revision Commission Meeting (June 21, 1989).

57. Eric Lane, Executive Director, Charter Revision Commission Hearing (May 10, 1989) (testimony) at 384-385.

58. Eric Lane, Executive Director 1989 Charter Revision Commission, Hearing on Legislation to Initiate New Charter Revision Commission hosted by the Committee on Governmental Operations, State & Federal Legislation, (Oct 30, 2024), (testimony).

59. Howard Slatkin and Ray Xie, “The Elephant in the Room: How ULURP’s Skewed Political Incentives Prevent Housing,” Citizens Housing & Planning Council, Feb. 2025.

60. Peter F. Vallone, Learning to Govern, (Chaucer Press, 2005), at 201.

61. New York City Council, LU 0170-1998: Zoning, Special Clinton District, Manhattan (980271ZRM).

62. David W. Dunlap, “Council’s Land-Use Procedures Emerging,” The New York Times, Jan. 3, 1993.

63. Jessica Katz, Manhattan Hearing, (Apr. 23, 2025) (testimony); Myers, Steven Lee, “New Yorkers Approve Limit of 2 Terms for City Officials, The New York Times, Nov. 3, 1993; New York City Council, Council Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito Announces Council Reform Package, Apr. 29, 2014.

64. New York City Council, Reso. 2020-2009, LU 1075 - Zoning Resolution, Special Permit to facilitate a mixed-use development on property located on the easterly side of Dock Street between Front Street and Water St. (C090184ZSK). The only ULURP of any kind to be approved over the objection of a local member since then was the Blood Center Rezoning in 2021—a life sciences project that would support blood services to the region’s hospitals and medical research. Deemed by many to be a project of citywide importance, that project proved to be the rare case where councilmembers were willing to vote in favor of a project despite local opposition. See Gabriel Poblete and Jeff Coltin, “Is the New York Blood Center approval the end of City Council’s Member Deference?,” City and State, Nov. 23, 2021.

65. Staff analysis, excludes Urban Development Action Area Projects (UDAAP).

66. Antonio Reynoso, Brooklyn Borough President, Brooklyn Hearing (Feb. 11, 2025) (testimony) at 60.