New York City faces what is likely the worst housing affordability crisis in its history. The effects touch every New Yorker and reverberate around the region, state, and country. Whether you are a lifelong New Yorker struggling to remain in your community, a young family looking to buy a home, or a newcomer seeking an apartment close to a job, the challenge of finding a safe, stable home seems to grow more difficult by the hour.

The housing crisis shapes what kind of city New York will be. It damages the local economy.1 It hurts the city’s standing on the national and international stage. And it undermines New York’s promise as a city of strivers, creatives, and entrepreneurs, sapping the vitality that has made the city a world center of business, arts, and culture.

The crisis also shapes who New York City will be for. It drives gentrification, displacement, segregation, and tenant harassment. It forces working New Yorkers with full-time jobs into homelessness. Family, friends, and caretakers double up in overcrowded homes. Nearly every New Yorker has said goodbye to a loved one or neighbor leaving our city in search of a more affordable one.

New York has long understood that the root of its housing crisis is a shortage of housing. Since 1960, New York City has been in a declared “Housing Emergency,” defined as when the vacancy rate is below 5%.2 Today, the City suffers from a net rental vacancy rate of 1.4%—lower than almost any time since that emergency was declared.3 Open houses for available apartments are met with lines down the block.4 When applications for Section 8 housing vouchers opened last year, over 600,000 people applied to be added to the waitlist in a week.5 For those lucky enough to secure a voucher, nearly 50% of families fail to find an apartment where they can use it.6

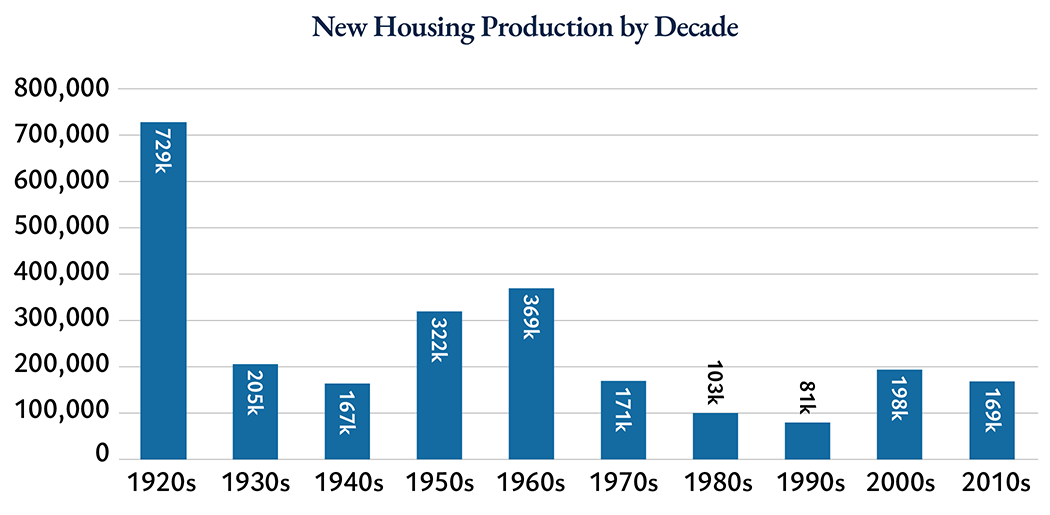

In many ways, New York City is a victim of its own success. Over the last few decades, a growing economy, coupled with historic decreases in crime and improvements in city services and amenities, has fueled demand to live in our city. But housing production has not kept up. From 2010 to 2023, for example, the city created more than three times as many jobs as new homes.7

That mismatch between the supply of housing and demand to live here creates a cruel game of musical chairs. Higher-income households attracted to the city by jobs and amenities outbid lower-income New Yorkers for new and old housing alike. Under these conditions, the city’s success in creating good-paying jobs and lowering crime simply drives rents up further, chipping away at wage gains for all workers and dulling the opportunity that should be the city’s calling card. Today, more than half of New Yorkers pay more than 29.5% of their income towards rent. For New Yorkers making less than $70,000 a year, the average family spends 54% of their income on rent.8

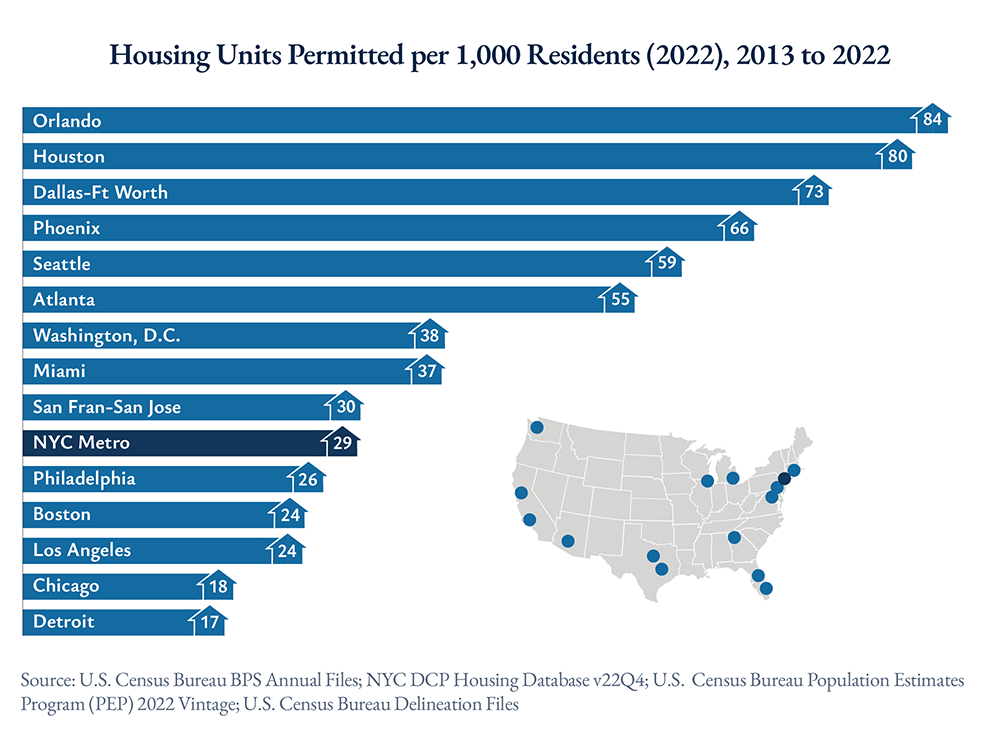

New York’s housing shortage is especially acute, but the problem is national. And there is a virtual consensus among experts, from across institutions and disciplines, that a lack of housing production is a fundamental driver of this growing national housing crisis.9 While calculating just how much housing New York City needs is an inexact science, multiple recent estimates have found that, over the next ten years, the city is about 500,000 homes short of a healthy housing market, where costs are stable, families and individuals have options, and the city and its economy have room to grow and change over time.10 To put this number in perspective: In recent years the city has enjoyed relatively high housing production, but it still builds only about 25,000 homes per year—about half of its overall need.11

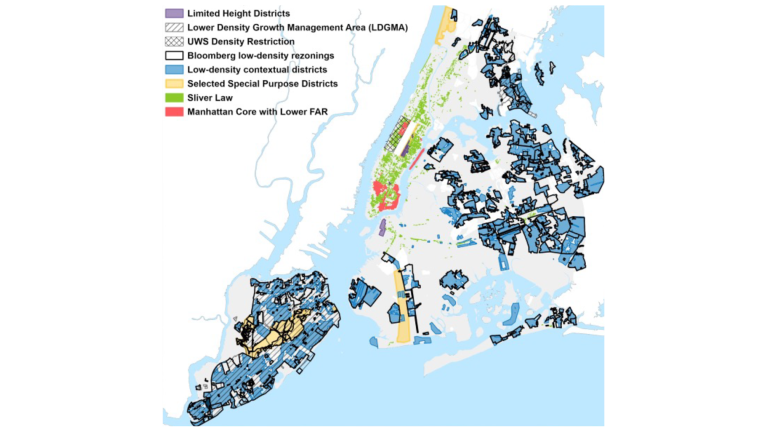

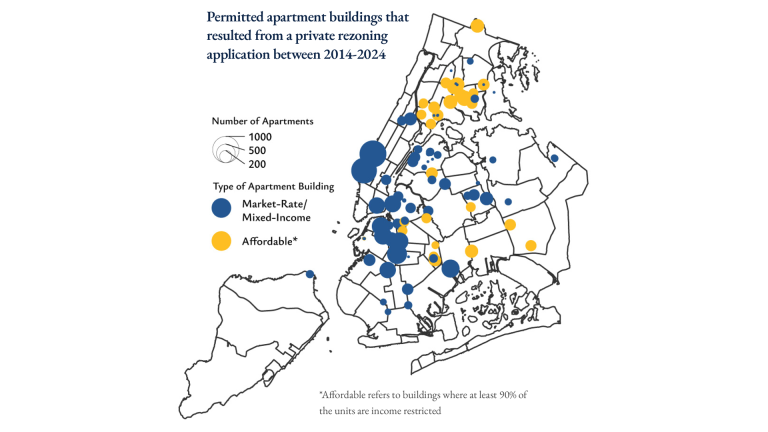

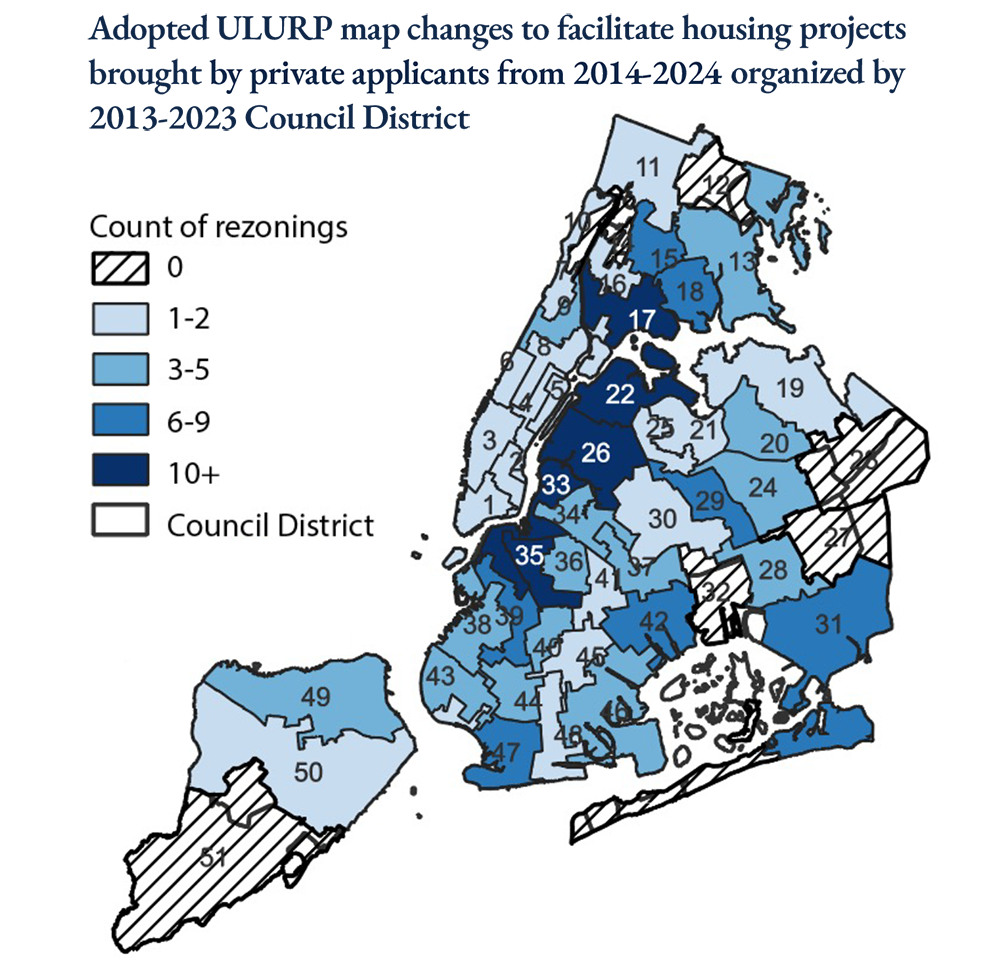

What’s more, the housing that has been produced in recent decades is spread unevenly across the city. From 2014 to 2024, 12 Community Districts added as much housing as the other 47 combined.12 While some neighborhoods see transformative levels of housing production, others—like portions of the Upper East Side, the West Village, and SoHo—have lost housing in certain years due to a combination of restrictive land use regulations and affluent New Yorkers combining apartments into larger homes.13

Despite these challenges, local government has much to be proud of. By many measures, the City does more than any other in America to build and maintain affordable housing. New York finances more affordable housing (~25,000 units per year) than many countries.14 New York City’s public housing system (~177,000 units) is an order of magnitude larger than any other city, and New York remains committed to its system when other cities have abandoned the project of public housing altogether.15 New York boasts some of the strongest tenant protections in the nation, and some one million rent-stabilized apartments provide a critical source of affordability.16 The trouble is that New York’s housing shortage is so great that even these efforts cannot by themselves tame the crisis.

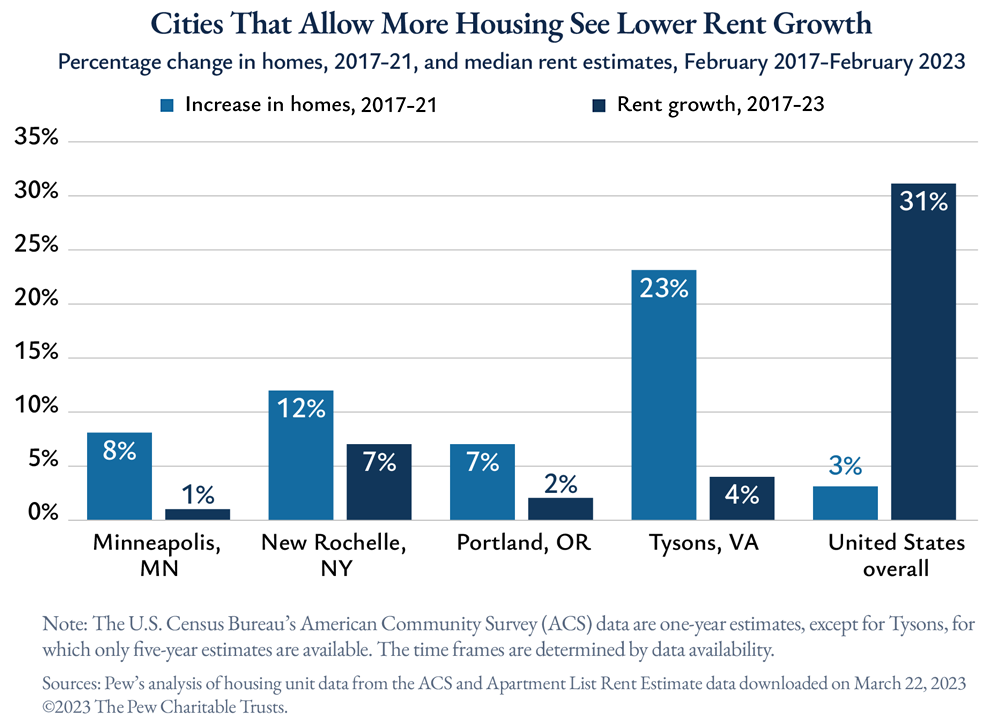

New York’s own history shows that it can grow while preserving housing affordability—in midcentury decades, it did just that. Other cities and metro areas are also successfully holding housing costs down—or even lowering them—by producing more housing than we do, even as their populations grow more quickly than New York’s.

In other words, both our own history and examples from around the country confirm that if we build more housing, we can meaningfully lower housing costs. But addressing the housing crisis is about more than lowering the rent. Today, the City’s failure to tackle the housing crisis threatens to worsen racial and economic segregation, sap economic dynamism, and diminish New York’s presence on the national stage.

A Segregated City

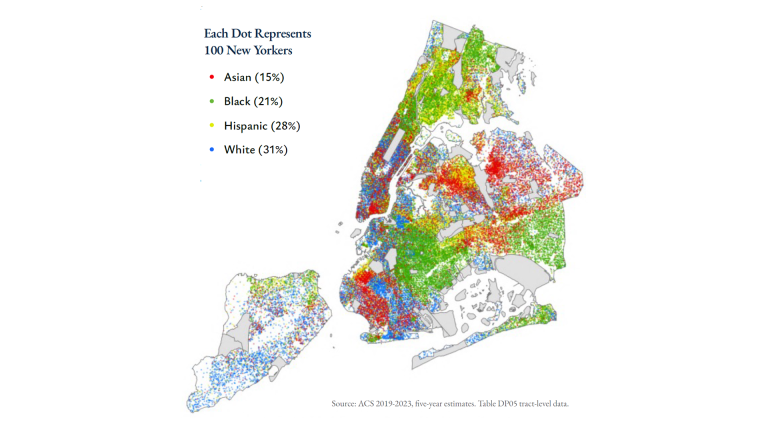

While New York City has made significant strides in promoting fair housing in recent decades, the city and surrounding region remain one of the most racially segregated major metropolitan areas in the country.17 This segregation is in large part the result of government actions going back centuries.18

While New York City is incredibly diverse, many of its neighborhoods are not. Overall, no racial or ethnic group comprises more than roughly a third of the city’s population. But most neighborhoods have a clear racial or ethnic majority group, and only 5% of New Yorkers live in a neighborhood where all of New York City’s diversity has meaningful representation, with Asian, Black, Hispanic, and white New Yorkers each comprising at least 10% of the neighborhood.19 Economic segregation, which is deeply interconnected with race, also persists. While poverty levels have fallen in some areas, most areas of concentrated poverty and wealth have remained consistent.20 This segregation is not just in tension with our city’s ideal as a melting pot—it also has real-world, lasting consequences. Research indicates that the zip code a child grows up in is a determining factor in nearly every facet of their life.21

Tight housing markets give landlords the ability not only to charge high rents, but also to discriminate based on race, family status, source of income, credit rating, justice-involvement status, or any other arbitrary whim of a landlord. When there are dozens or even hundreds of applicants for individual apartments, landlords have enormous power and discrimination is very hard to detect and enforce against, regardless of what the law says.

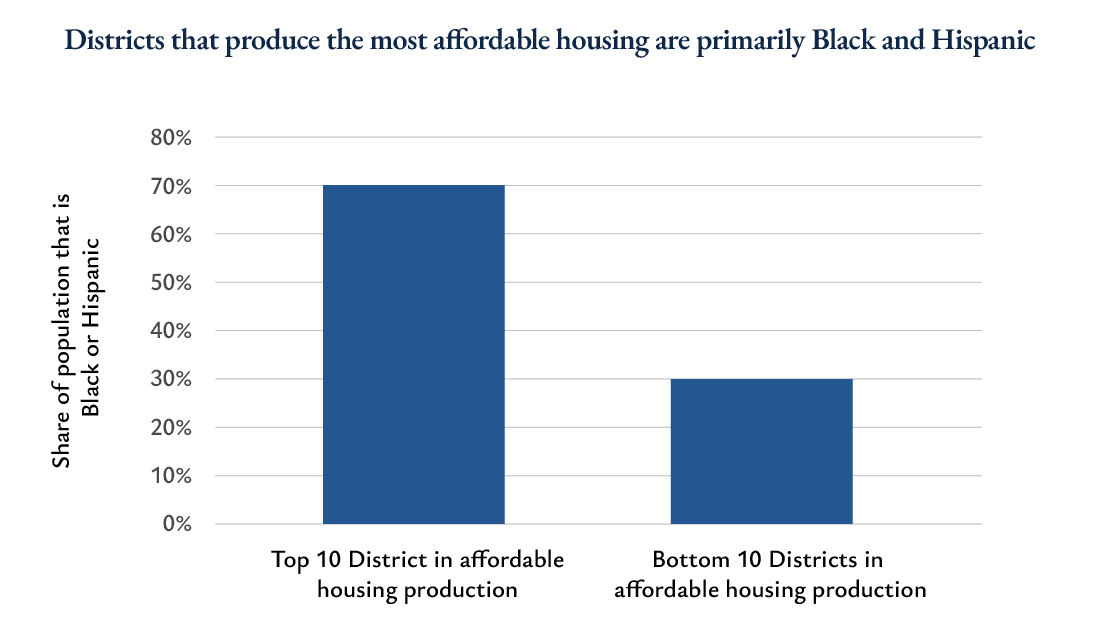

The development of new housing, and particularly affordable housing, is a critical tool for promoting integration and housing mobility. And because low-income, Black, and Hispanic New Yorkers are especially in need of affordable housing, developing more affordable housing preserves these communities’ ability to call New York home.23

But affordable housing cannot be built where it is illegal to build housing. Today, the neighborhoods that are most effective at preventing new housing also tend to be those that have little existing affordable housing. The Community Districts producing the most affordable housing are disproportionately Black and Hispanic, and the districts producing the least affordable housing are disproportionately white. These patterns of development can entrench segregation and limit the housing choices that serve as the guiding tenet for the City’s Fair Housing policy.

24. New York Housing Conference, 2024 NYC Housing Tracker Report, June 2024.

A Less Dynamic City

New York City’s housing crisis is felt most acutely by the low-income families that struggle to find shelter, but it ripples through the entire economy. The housing shortage makes it hard for employers to hire and retain talent in New York City. A recent estimate of the cost of the housing crisis for the New York Metro area found that it will cost the region nearly a trillion dollars in lost economic activity over the next 10 years.25 Others have estimated nearly $20 billion in annual gross city product lost due to the economic drag of limited mobility for workers.26 When New Yorkers move, but keep their jobs in the city, the city loses hundreds of millions of dollars in income taxes.27 Similarly, New York misses out on significant property tax revenues from properties that could be redeveloped, but instead sit fallow.

Meanwhile, quintessential New York City industries struggle to make do. Over the last decade, New York City’s fashion industry has declined by nearly 30% driven in part by the “high costs of living and doing business.”28 New York City’s arts scene is still the most vibrant in the world, with more museums, theatres, and galleries than anywhere else, but new artists are struggling to find a place to get their start. Even the tech industry, with its relatively high salaries, struggles to recruit in New York due to high cost of living.29 The Theme from New York, New York, “If I can make it there, I'll make it anywhere” has never been more true.30 Because it’s harder than ever to make it in New York.

A Waning National Presence

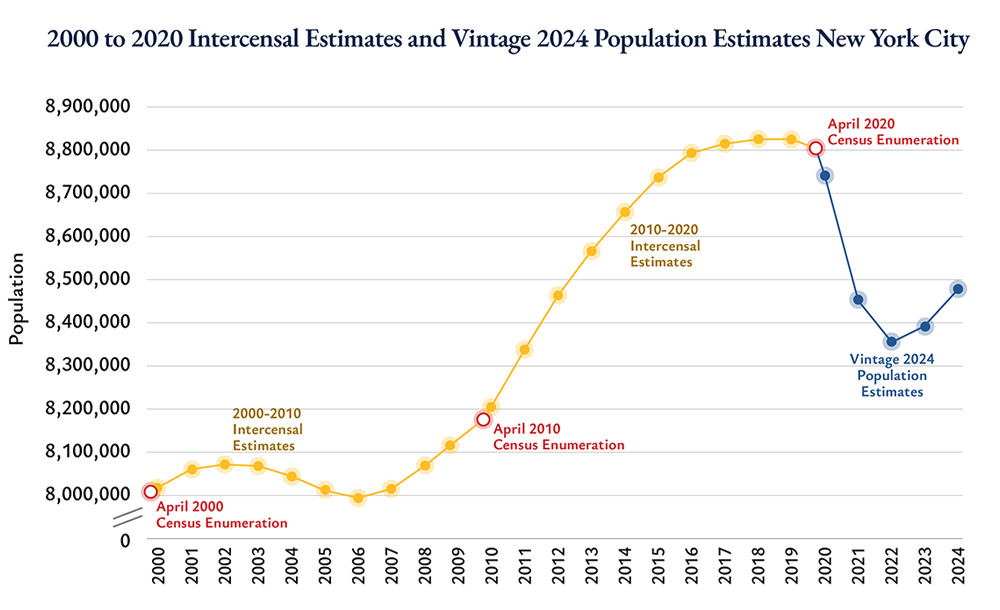

Recent reports of New York City’s population decline have been exaggerated, but the city’s growth was slowing even prior to COVID.31 That declining growth will have significant implications for New York City’s future on the national stage.

In 1960, the last time New York City comprehensively changed its land use policy, New York voters elected 9.5% of the House of Representatives.32 Today, New York elects only 6%, with recent population estimates suggesting New York will lose another two seats by 2030.33 This trend highlights a broader shift in New York City’s history, with the city growing more slowly than the country at large.

The result is a city with less and less say in our nation’s capital. So long as the city continues to rely on the federal government for support—from investments in NYCHA, to new subway lines, health care, and more—maintaining a meaningful federal presence is critical. To retain its power on the national stage, New York City must embrace, and plan for, growth.

34. Department of City Planning, New York City’s Population Estimates and Trends, March 2025.

Causes of the Housing Crisis

Many areas of policy affect our city’s housing affordability crisis. But not all are within the power of local government to change or within the scope of the City Charter.

Tenant protections and the city’s immense stock of rent-stabilized housing both play a critical role in maintaining affordability for New York families, but are largely creatures of state law. Property taxes—which affect homeowners, renters, and builders alike — are similarly defined by state law and difficult to address through the Charter. Federal support (or the lack thereof) has played an enormous part in the development and maintenance of the City’s affordable and public housing stock but likewise cannot be addressed through the Charter. In these and other areas, the City cannot always control its own destiny.

But zoning—which determines what types of housing we can build and where we can build it—is one of the most direct causes of the housing shortage, is fundamentally within the City’s control, and is closely linked to the structure of the City Charter.

Zoning and the Housing Shortage

The housing shortage is not a new phenomenon. It has evolved over decades through a series of policy decisions—large and small, witting and unwitting—that have limited our housing growth.

As in cities across the country, New York City policymakers enacted increasingly restrictive land use regulations in the latter half of the 1900s, steadily limiting how much New York could grow. The most dramatic restriction was the adoption of a new citywide Zoning Resolution in 1961, which significantly reduced how much housing could be built in nearly every part of the city. By one measure, looking at how many people could theoretically be accommodated within the city, the 1961 update reduced the city’s population capacity from 55 million to 11 million.35 In one fell swoop, the ubiquitous 6-story apartment building—a workhorse of affordable housing that defines the built context in countless outer-borough neighborhoods—was outlawed in most areas.

Across all of New York City, fewer than 4% of properties have historic preservation protections, and in certain historic districts the conversion of office and commercial buildings into housing has increased the number of homes while maintaining and protecting the neighborhood’s character. But about 30% of Manhattan lots are restricted by historic districting, and many of these higher-market areas have struggled to produce new housing.38 Significant numbers of apartments have been combined, offsetting any gains from redeveloping non-historic properties and leading to housing loss in some areas.39

Although zoning is not the only factor that impacts the amount of housing New York builds, it is the clearest cause of limited housing production in recent decades and the one that the city has the most control over. Other cities and regions with more liberal zoning rules have seen much greater housing production than New York in recent years, despite facing similar economic conditions, including interest rates and tax environment. Just across the Hudson, Jersey City added nearly 26,000 units between 2010 and 2022, triple the per capita production of the New York metro area.40 And while New York does face meaningful challenges, including the availability of land and rising construction costs, the fact that some parts of the city grow at a brisk pace while nearby areas languish under restrictive zoning shows that land use regulation today prevents housing construction where it would be feasible if it were only allowed.41

Land Use Review Process and Member Deference

If New York is to reverse the underproduction of housing that has driven its housing crisis, the City must make it easier to build housing. Unfortunately, increasingly restrictive land use regulation has meant that more builders, both public and private, need to apply for zoning changes or other discretionary approvals to build.

Not coincidentally, the procedures to change zoning have gotten significantly more onerous and unpredictable over this same period. The process for changing zoning, which is set out in the Charter, is a key connection between the housing crisis and the Commission.

Calls for more community control and a turn away from central planning in the post-Urban Renewal era led to the creation of the Uniform Land Use Review Procedure (“ULURP”) by the 1975 Charter Review Commission, with formalized Community Boards representing affected neighborhoods at the beginning of the process.

Once begun, formal ULURP takes about seven months to complete. The process begins with an advisory opinion from affected Community Boards, followed by an advisory opinion from an affected Borough President. Then a land use application proceeds to review by the City Planning Commission (CPC), followed by review by the City Council, and ultimately the Mayor. If the Council rejects a land use application, the Mayor can technically veto the Council’s decision, and the Council can overturn a Mayoral veto with a two-thirds majority.42 In practice, the CPC and the Council are decisive—Mayoral vetoes are exceedingly rare, in part because the Council would, for institutional reasons, overrule any Mayoral veto.

Originally, ULURP ended with the Board of Estimate (BOE), a hybrid executive-legislative body comprising the Mayor (two votes), Comptroller (two votes), City Council President (two votes), and the Borough Presidents (one vote each). ULURP represented a move toward formal neighborhood participation in land use decision-making, and a move away from the top-down master planning that characterized the Urban Renewal era. But the structure of the BOE encouraged a broad perspective on land use issues. Citywide officials held a majority of votes—six out of eleven—and the smallest jurisdiction represented was the borough.

If a local member decides against a proposal, other members of the Council will agree to oppose it, and the proposal will be rejected. If the local member opts to support the proposal, it will be approved. In essence, member deference is an agreement among councilmembers: each member will control land use in her district, and in return will not second guess the land use decisions of her colleagues.

To this point, member deference has been a significant focus of testimony before the Commission. Supporters of member deference argue it is vitally important that communities have a mechanism to shape proposals for development, and that member deference helps ensure land use changes are informed by local views.44 They maintain that member deference promotes political accountability in land use matters, with communities able to hold local members responsible for land use decisions and, if necessary, vote members out. They point out that members leverage their veto power to win concessions from those seeking land use approvals, including changes to the size of proposed developments, commitments to affordability, and various other community benefits.45 And they note that while member deference is practiced on district-specific land use proposals, the City Council recently enacted a historic city-wide zoning reform—City of Yes for Housing Opportunity—that, because it impacted every district, was not subject to typical member deference dynamics and opened up possibilities for new housing even in districts where members opposed the changes.

Critics of member deference, including former Councilmember and current Queens Borough President Donovan Richards, charge that it is a form of “municipal feudalism” that treats the local member like “a feudal lord who gets to arbitrarily rule over public land as though it were a personal fiefdom” irrespective of citywide needs.46 The overall result of member deference, critics argue, is a hyper-local planning process that deprives the city of sorely needed housing; drives inequitable patterns of development across the city; and, as Public Advocate Jumaane Williams has charged, perpetuates residential segregation.47 Critics also argue that member deference thwarts democratic accountability by depriving the residents of every other district of a say on projects that would address a citywide housing crisis.

Whatever its merits, member deference is today a powerful force, especially in housing. According to research by Commission staff, the last time a district-specific housing proposal was approved through ULURP without the support of the local member was over 16 years ago.48

The Evolution of Member Deference

During the 1989 Charter revision process, which was tasked with reenvisioning how land use review would work without a Board of Estimate, many feared that giving the City Council final say over land use matters would give rise to a practice of member deference and stymie important land use changes. As then-Mayor Koch warned that Commission:

I fear that your proposal will give legislative legitimacy to the NIMBY reaction that now threatens to block any socially responsible land use policy. The legislative tradition of comity and deference, which grants one legislator, in essence, the power to determine the collective vote on matters affecting his or her district, means that any time a member of the City Council does not like a land use decision in his or her district, that member will have no difficulty mustering the required votes to take jurisdiction and vote it down. This is a sobering thought. We would run the risk of land use paralysis.49

The New York Times Editorial Board expressed similar concerns, warning that the Commission’s proposal “makes an expanded and inevitably more parochial Council the final arbiter on most land-use issues.”50 Eric Lane, the Commission's Executive Director, similarly warned that “If you require council approval of [a zoning change]...the Council member in whose district it would be would...basically be able to stop the project...[The legislature would] just give deference to the member whose district it is in.”51

In response to concerns about “land use paralysis,” the Commission had initially sought to give the newly empowered Council a role in broad citywide land use initiatives, like what would become City of Yes, but no role in particular, “project-specific” land use decisions. Ultimately, however, some members of the Commission felt that particularly controversial projects should receive political oversight from legislative body and numerous groups testifying before the Commission agreed.52 As such, the final Charter proposal reached a compromise, including both a “Fair Share” framework that would help evenly distribute undesirable municipal necessities (such as incinerators and garages) and the ability for the City Council to review any action under ULURP. Reflecting on that compromise in an appearance before this Commission, Executive Director Lane testified that he still regrets the 1989 Commission’s failure to include a “mechanism that would stop...individual members” from vetoing land use projects.53

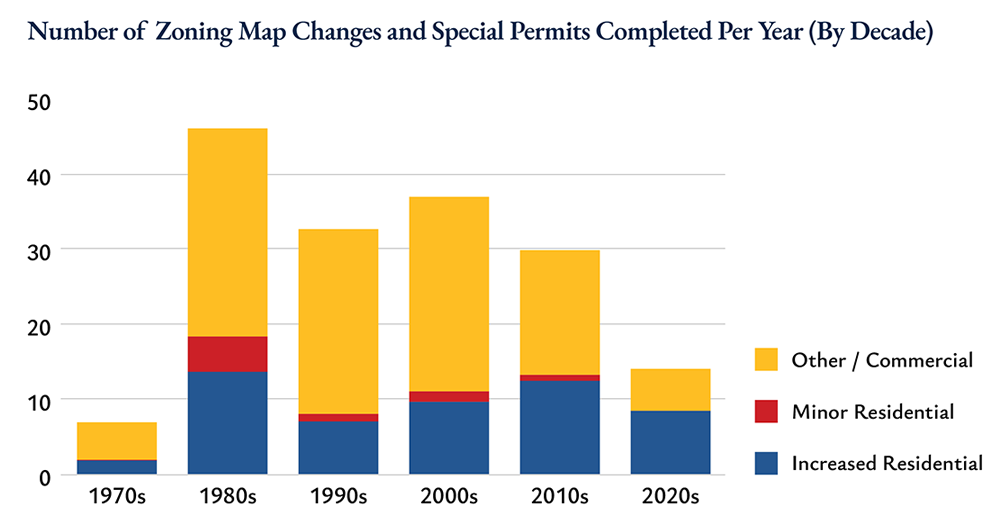

An analysis by the Citizens Housing & Planning Council (CHPC) suggests that the 1989 revisions led to an immediate drop in the number of rezonings approved in the immediate aftermath of Charter changes:54

55. Howard Slatkin and Ray Xie, “The Elephant in the Room: How ULURP’s Skewed Political Incentives Prevent Housing.”

In fact, the CHPC analysis found that “[d]espite an increasing share of housing-related ULURP applications, the volume of rezoning applications completed per year has never recovered to pre-1989 levels: so far this decade, rezonings are being approved at 61% of the pace during the 1980s, and the recent peak of the 2000s was still just 80% of the pre-1989 rate.”56 These findings suggest that, all else equal, the 1989 reforms made zoning for more housing harder than it used to be.

At the same time, the newly empowered City Council did not immediately develop the practice of “member deference” as it functions today. Instead, through the 1990s, land use decision-making was firmly controlled by then-Speaker of the City Council Peter Vallone, who supported multiple rezonings over the wishes of local councilmembers.57 As the New York Times put it: “There are many more participants than before [in the land use process]. Yet the Council is much more firmly under the control of one person.”58

Around the turn of the millennium, the practice began to change, with members overruled fewer and fewer times. Some practitioners attribute this change to the introduction of Council term limits, to City Council rules reforms that may have weakened the Speaker’s ability to influence individual members, and to a change in general political attitudes toward new housing, as development pressures accelerated in the 2000s.59

Examples of Member Deference Being Over-Ruled in ULURP Actions Since 2000:60

| Year | ULURP # | Description | Category |

| 2021 | 210351ZMM | New York Blood Center | Commercial |

| 2009 | 090403 PSQ | New York Police Academy | City Project |

| 2009 | 090184 ZSK | Dock Street Development | Residential / Mixed-use |

| 2009 | 090415 HUK | Broadway Triangle Rezoning | Residential / Mixed-use |

| 2009 | 090470 PPQ | College Point Corporate Park | Commercial |

| 2007 | 070315 (A) ZRQ | Jamaica Rezoning | Residential / Mixed-use |

| 2007 | 20095400 SCQ | Maspeth High School | City Project |

| 2004 | 040217 ZSK | Watchtower Development | Residential / Mixed-use |

| 2004 | 040445 ZSM | Harlem Park Hotel | Commercial |

| 2003 | 030158 PSK | NYCEM Headquarters | City Project |

| 2002 | 010602 ZSM | Special Permit for a Manhattan Parking Garage (Upper West Side) | Other |

| 2001 | M 820995 | Hotel near La Guardia Airport | Commercial |

Whatever the reason, after 2000, there are only a few major examples of members being overruled—typically non-residential projects like a police academy in Queens whose citywide importance were more legible. The last housing project to be approved through ULURP over the objection of a local member was in 2009—16 years ago.61

Today, member deference is firmly established. And because the views of the local member are decisive, the most critical phase in public review of a land use proposal has become the effort to win the local member’s support. In this way, member deference has come to serve as one of the foremost ways that local priorities—channeled through a community’s elected councilmember—shape proposals for development. In 2021, for example, then-Councilmember and now-Comptroller Brad Lander used his position to negotiate a broad set of neighborhood investments as part of the Gowanus Neighborhood Rezoning, including investments in local infrastructure and public housing, in return for his approval of a plan to add some 8,000 new apartments.62

Often, members use their power to reduce the size and scale of proposed development to respond to local concerns. A proposal for housing at 80 Flatbush Ave. in Brooklyn—a project to add new housing, schools, and cultural space—was approved in 2018, but only after the local member negotiated changes that reduced the height of development allowed on the site, and, consequently, the amount of housing it would deliver.63

Elsewhere, councilmembers frequently use their power to block housing proposals altogether. The opposition of one former councilmember led to the withdrawal prior to a Council vote of three separate housing proposals in just ten months: 1880-1888 Coney Island Avenue64, 1571 McDonald Avenue65, and 1233 57th Street.66 Together, these three projects would have created 397 homes, including 115 affordable homes, in a Council district that saw the creation of just 182 affordable units total from 2014-2023.67

Land Use Proposals to Begin ULURP Since 2022 that Were Withdrawn, Rejected, or Modified

| Units as Originally Proposed | Income-Restricted Affordable Units Proposed | Units Approved | Affordable Units Approved | ||

| Projects Certified and Withdrawn, or Voted Down | 9 | 1,790 | 678 | 0 | 0 |

| Projects Approved with Modifications | 18 | 11,493 | 3,067 | 9,736 | 2,820 |

| Total Homes Lost: | 3,547 | ||||

| Total Income-Restricted Affordable Homes Lost: | 925 | ||||

These examples are a part of a broader trend. Based on an analysis of land use proposals that formally entered ULURP since 2022, some 3,547 units overall have been lost as a result of Council modifications to the scale of housing proposals or the withdrawal of housing proposals in the face of opposition.68

Notably, every one of these projects was slated to deliver affordable housing under the City’s mandatory inclusionary housing policy, or other City policies.69

The Housing That Isn’t Built

The most significant consequence of member deference is, however, the most difficult to measure: the projects that are never even proposed. As the Citizens Budget Commission has explained, “it is impossible to estimate how many projects never g[et] proposed or fail…to advance beyond informal conversations because of the cost, length, and uncertainty of the land use decision-making process.”70 If a potential project is in a district where a local member is likely to be hostile to new housing, it rarely reaches the filing stage. The costs of moving through the land use process — including upfront costs like environmental review, consultants, attorneys, and lobbyists — are so high that it does not make sense to initiate a land use proposal if the odds of approval are remote.

As Kirk Goodrich, President of Monadnock Development, a Brooklyn-based builder of affordable housing, has explained:

If somebody calls me as a developer about a site…to build affordable housing of scale, literally the first thing I do is I figure out who the councilmember is. Because if the councilmember is resistant to an entitlement or rezoning…then it is dead on arrival. And no developer is going to spend time and money they can’t recover on an entitlement process when they know out of the gate that the councilmember is clearly opposed to it.71

Or as Borough President Antonio Reynoso put it, there are “councilmember…district[s]” where “they shut down every single project before it even starts.”72 Indeed, an analysis of private applications for rezonings to enable housing over the last decade reveals that some City Council districts saw no applications at all, and only 5 of the city’s 51 Council districts averaged more than a single application per year.

73. Staff Analysis of rezoning applications based on Zoning Application Portal dataset

Member deference deters so much housing production because councilmembers—whose jobs depend on the voters of their district and those voters alone—have powerful political incentives to reject new housing. Members have personally recounted to Commission staff that while they believed certain housing proposals were in the best interests of their constituents and the city, they could not vote to approve them for fear doing so would poison their relationship with important local constituencies and jeopardize their odds of reelection.

The account of former Councilmember Marjorie Velázquez, who testified before the Commission, underscores the often-extreme pressure that councilmembers face to reject housing. Velázquez testified that during public review of a housing rezoning proposal in her district, she received multiple death threats from opponents of a project, had her home burglarized, was forced to obtain police protection for herself and her staff, and even needed a panic button installed in her home to alert the NYPD of threats to her safety.74 Both Velázquez and political observers broadly attribute her support for the housing proposal as the reason she was defeated at the following election. As Citizens Housing & Planning Council summarized: “There are some elected officials who have taken heroic steps to approve housing and the zoning to enable it...But if it takes heroes to get housing built, we will never build enough housing.”75

New York is not alone in having a system like member deference. In Chicago, which has a similar district-based legislative branch with a role in land use, the practice is known as “aldermanic privilege.”76 In 2023, an investigation by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development found that Chicago’s practice disproportionately harms Black and Hispanic households, perpetuates residential segregation, and effectuates opposition to affordable housing based on racial animus.77 These dynamics give credence to the warning of then-Councilmember and now Public Advocate Jumaane Williams, who argued that, by giving local legislators who represent segregated communities the power to block housing, “member deference...continues the segregation of the city.”78

Other Process Costs

Even before ULURP formally begins, there is a lengthy period known as “pre-certification” that is often far longer than ULURP itself. State law—namely, environmental review requirements—is the leading reason why pre-certification has become so long. Today, according to the most recent Mayor’s Management Report, only 61% of simple zoning actions entered public review within 12 months of starting pre-certification in Fiscal Year 2024 (FY24).79 Of more complex projects requiring an Environmental Assessment Statement or EAS, only 32% entered public review within 15 months in FY24.80 As for the most complex projects, requiring an Environmental Impact Statement or EIS, 89% entered public review within 22 months in FY24.81

In New York, as across the United States, policymakers began to create a process for environmental review of government actions during the 1970s. Following the federal passage of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) in 1970, New York State passed the State Environmental Quality Review Act (SEQRA) in 1975, and the City built upon that with the establishment of City Environmental Quality Review (CEQR) in 1977.

These rules and processes have changed significantly in the last five decades, growing in scope and intensity, often in response to litigation.82 It is now common for large projects to spend seven figures and multiple years on environmental review, covering categories that are far afield from “environmental issues” as commonly understood.83 In this way, CEQR now frequently serves as a protector of the status quo, even when the status quo inhibits the city’s ability to address and adapt to climate change, promote resiliency in flood-prone communities, expand clean energy, and build critically needed housing.84 Because, however, environmental review is largely a creature of state law, not local law, the Commission’s ability to reform this process is limited.

The growing length and cost of the pre-certification process mean that someone seeking land use changes in order to build housing must be able to withstand years of costs and payments to consultants or lawyers who are superfluous to the actual construction of the housing. Testimony before the Commission from the Citizens Budget Commission suggests that this dynamic increases the cost of a project by 11 to 16%, reaching over $80,000 per new apartment.85 These costs, like actual construction and labor costs, are ultimately carried through into the price of housing, and deter many projects from being proposed at all.

In practice, the costs of moving through the land use process mean that applicants will only pursue land use changes if the end result will be a development large enough to make the years of pre-construction costs worth it. The result is that land use changes have become synonymous, in the eyes of many, with a particular kind of development: proposals for new housing that are large and luxe—because these are the only kind of projects for which ULURP is feasible.

This selection bias can be seen in the types of land use changes that private landowners have applied for. A staff analysis of rezonings over the past decade found that only one application in more than 120 private applications sought an increase in residential density of less than 40%. Only one additional application sought a change to a “low-density” district, defined as R5 or lower. Instead, the typical application seeks to double or triple residential density.

In short, because land use changes require a long and uncertain process replete with consultants and lawyers’ fees, only large projects are ever proposed and built—creating more tension and conflict between communities and homebuilders, public or private, than necessary. ULURP and its associated process requirements have essentially disqualified the modestly sized buildings that were the backbone of outer-borough housing production through much of the 20th century. These processes also effectively prohibit the kinds of incremental change that would enable neighborhoods to grow organically over time; changes that could avoid some of the angst that often attends the more dramatic proposals delivered by ULURP as it stands today.

Even after a builder has completed ULURP and has the right to build, there is a further source of delay and cost: the process of applying for and receiving the permits and inspections needed to initiate and complete construction. Every new apartment building in New York City, even those constructed “by-right” without a zoning change, require critical permits from a variety of agencies including the Department of Buildings, Department of Environmental Protection, Department of Parks & Recreation, and the New York City Fire Department. These permits ensure fire-safety, compliance with the building code, the state Multiple Dwelling Law, accessibility requirements, and many other key city priorities.

However, obtaining these permits can be a lengthy process. From 2010 to 2023 the average time to be granted a building permit for a new residential building of five or more units was 1.5 years. Ultimately, the total time between initial plan filing and building occupancy was four years.86 New York City has examined this issue closely over the last few years as part of the Get Stuff Built initiative. Get Stuff Built identified 47 key reforms to improve the permitting process in New York City. However, only eight of those 47 reforms required a change beyond just operations within existing mayoral agencies and all were permissible via action by local law passed by the City Council.87

While further improvements to the permitting process are critical, following extensive internal discussions and consultation with stakeholders, Commission staff believes that this important subject is not amenable to effective intervention through the Charter. Instead, improvements in agency technology and coordination, as well as local law changes that do not require Charter amendments, are needed.

Mayor Lindsay, community members and construction workers at St. Nicholas Avenue and West 118th to announce the rehabilitation of the Garden Court apartment building.

Areas to Explore

The New York City Charter protects the foundational architecture of the land use process from ordinary politics, and so the only way for the City to reconsider and adjust key aspects of the Charter that govern land use is through a direct vote by the people.

The framers of the 1989 Charter showed remarkable foresight and civic wisdom in the land use arena, giving close attention to the balance between neighborhood perspectives and citywide needs, all in a procedure with guaranteed access and clearly defined timelines. To the wisdom of the 1989 Charter, we can now add some 36 years of experience. Decades have helped illuminate what ULURP and other Charter-defined structures and procedures do well, what they do less well, and what aspects may warrant reconsideration to address pressing challenges facing our city.

The Commission has heard significant testimony suggesting tweaks and changes to ULURP. That the Commission has not heard significant testimony suggesting that ULURP be replaced wholesale is a testament to its enduring success over the last 50 years at incorporating meaningful public input from a variety of stakeholders, while clarifying and standardizing the application process and review timeline for those, both public and private, who seek land use changes. Instead, the Commission has broadly heard two sets of concerns about the current New York City land use process:

First, the Commission heard from experts, practitioners, and members of the public who explained that ULURP has resulted in development patterns that are very uneven across the city. A few neighborhoods produce the majority of affordable housing, others build mainly market-rate housing, and some produce no housing at all. For the reasons discussed above, these dynamics contribute to rising costs, segregation, displacement, and gentrification.

Second, the Commission heard about the barriers New York City agencies face in delivering valuable projects for New Yorkers. From building affordable housing on City-owned land, to partnering with private actors to build affordable housing on private land, agencies often contend with excessively complex and lengthy processes that hamper their ability to deliver change at scale.

Across these two issues the Commission was grateful to receive numerous opinions from elected officials, policy makers, academics, activists, and other members of the public. Their suggestions fell into three primary categories:

Reducing Process Costs: The Commission heard from experts and the public who explained that ULURP does not work for modest projects, due to the costs associated with an application process than can take anywhere from two to five years, or even longer for complex projects. Today, ULURP frequently requires the same costly multi-year process of environmental and land use review for a new eight-unit apartment building as for an 800-unit apartment building. As such, ULURP applications tend to be for big changes rather than small ones, leaving lower density parts of the city practically ineligible for small scale residential development or modest zoning changes over time. Similarly, the Commission heard the importance of making sure that ULURP works effectively for City-aided projects, like publicly-financed affordable housing, many of which require multiple overlapping processes.

Elevating Citywide Needs: The Commission heard testimony about the need to re-center citywide perspectives in areas of the city where ULURP manifestly fails to do that today. Many who testified before the Commission noted that, in certain geographies, the current process effectively gives not just a voice but a veto to affected neighborhoods on issues of citywide importance. This dynamic exacerbates uneven and inequitable patterns of housing development and results in ever-increasing burdens on areas of the city that allow for new housing development. Experts testified that these patterns are even more pronounced for City-aided affordable housing projects.

Leveraging Public Land: Finally, stakeholders testified to the Commission about challenges with activating public land to support affordable housing production in New York City, as well as challenges with other dispositions and acquisitions affecting residential property. In this area, experts identified areas of the Charter that could better promote the expeditious and efficient use of public land across the city.

Reducing Process Costs

Today, ULURP simply does not work for more modest changes to zoning. Small projects cannot support two or more years of pre-application delay, environmental and land use review, and other associated costs. Only large projects, resulting in a doubling or tripling of capacity, can sustain the costs and risk associated with ULURP.

As a result, zoning on a given site is either frozen in place or subject to a doubling or tripling of capacity, leaving out a vast “missing middle” of more modest zoning changes that could help neighborhoods adapt and change organically over time, serving citywide imperatives without triggering the level of resentment and anxiety that large zoning changes frequently occasion today. And by limiting opportunities for smaller projects, ULURP serves as a significant barrier to entry for smaller builders, like minority-and-women-owned business enterprises. As Kirk Goodrich told the Commission, “the reality is that…because it costs so much and takes so long, you can’t really expect anyone who is a fledgling developer or somebody who's not a multi-generational developer to be involved in this at all.”88 Instead, ULURP favors a small number of large and well-capitalized firms who can secure the lobbyists, lawyers, and consultants needed to navigate the City’s labyrinthine process.

In the last ten years in New York City, there were over 120 rezonings by private applicants to increase residential density. While dozens of these doubled, tripled, or quadrupled residential capacity by rezoning to medium- and high-density districts (R6 to R10), only one of those rezonings increased residential capacity by less than 40%. Only two rezoned to a lower-density district (R1 to R5) when increasing housing capacity. The numbers are clear: for modest increases and changes within low-density areas, ULURP is broken.

To that end, and in light of the extensive testimony on this topic received to date, the Charter Revision Commission may wish to explore modifications to the Charter that can reduce process costs for modest projects.

The Commission has received testimony on several possible approaches to reducing process costs, all of which the Commission may consider in the months ahead. Broadly speaking, these approaches include: A less time- and cost-intensive “fast track” land use review procedure for defined categories of actions and projects; a “zoning administrator” function with the power to approve defined categories of actions and modest zoning changes administratively; and general small adjustments to streamline ULURP.

“Fast Track” Land Use Review Process

One focus of testimony has been proposals to create a new “fast track” review for modest zoning changes and other land use applications that the time and money associated with ULURP effectively block today. Under this approach, ULURP would remain in place for most of the projects that go through ULURP today, but a more junior review would apply to more junior changes. A “fast track” procedure could also expedite particularly crucial or categorically beneficial applications and projects that go through ULURP today but may not necessitate such extensive review.

On a fast track for more modest projects, the Commission has received testimony from the Municipal Art Society, the Historic Districts Council, and others suggesting an alternative process for projects below defined thresholds that would retain critical opportunities for public input, but could help facilitate projects that do not happen today.89 The nature of the recommended thresholds has varied. Some have suggested absolute thresholds—for example, upzonings that remain within the low-density family of districts (R1-R5), or that remain within certain height and density limits near transit, could access a modified land use review procedure that is less intensive than full ULURP. Others have proposed relative thresholds—for example, zoning changes of less than a certain percent increase in residential density could qualify for streamlined process. The Commission also received testimony that the Charter should align a fast-track land use review procedure with CEQR “Type II” projects, which are categorically deemed not to have impacts and thus exempt from environmental review.

Any of these proposals would create an avenue for modest zoning changes that are relatively rare today. As discussed above, only two private ULURP applications out of over 120 have resulted in the type of modest development that such a “fast-track” could enable.

In a similar vein, the Commission has received testimony that defined categories of other ULURP actions, such as special permits for residential projects, should be able to access a streamlined process. As above, ULURP would remain in place for many or most special permits that go through ULURP under the existing regime, but modest, crucial, or categorically beneficial projects could access a new pathway. This proposal echoes some of the discussion around special permits and other actions in 1989, when the Commission debated whether the City Council—as New York City’s legislature—should have jurisdiction over “adjudicative” project-specific approvals like special permits or dispositions as opposed to “legislative” changes to the zoning map or text. The 1989 Charter Commission added these actions to the Council’s purview relatively late in the proposal development phase, owing largely to political calculation as opposed to specific policy considerations.90

The Commission has also received testimony recommending a “fast track” process for defined categories of projects, rather than defined categories of actions. The most popular suggestion, made by several parties testifying to the Commission as well as in written submissions, is to provide streamlined approvals for affordable housing projects. In that vein, the Commission received testimony from the Citizens Housing & Planning Council, the Regional Plan Association, and others that the Charter should create a Board of Standards and Appeals action that would allow zoning waivers for Housing Development Fund Companies—regulated entities that build affordable housing—upon making certain findings.91

The nature of the process changes recommended for such projects varies. Some recommendations focused on whether City Council review is necessary for smaller zoning changes and land use applications unlikely to raise significant planning concerns. In those instances, input from Community Boards and Borough Presidents and review and approval by the City Planning Commission may be sufficient to ensure appropriate planning outcomes. Others have suggested preserving the City Council’s role while bypassing the City Planning Commission. Others have suggested giving Borough Presidents final say over defined categories of actions or projects.

In considering these and other potential approaches, the Commission may consider both the benefits of simplifying public review for certain categories of modest, crucial, or categorically beneficial projects, and the need to ensure that any new public process is transparent, responsive to both local and citywide needs, and consistent with principles of democratic accountability.

Zoning Administrator

An alternative approach to streamlining the review process for defined categories of actions or projects is to introduce the role of zoning administrator, a recommendation made to the Commission by multiple parties. Zoning administrators are appointed individuals who have been a common element in the structure of land use administration in jurisdictions across the country since the advent of zoning over 100 years ago. The report that preceded the 1961 Zoning Resolution recommended adoption of a zoning administrator role within New York City’s land use decision-making structure. That aspect was not ultimately adopted and James Felt, City Planning Commissioner during the adoption of the 1961 resolution, would later write that “even more than before…New York needs a Zoning Administrator.”92

While powers and duties of zoning administrators vary significantly among jurisdictions, they often have authority over classes of conditional and special use permits and other actions that in New York City fall under various certifications (which go to the Chair or the CPC), authorizations (which go to Community Boards and CPC), and special permits (which receive full ULURP). In some jurisdictions, zoning administrators have authority over defined categories of modest zoning changes. Also common are fact-finding roles that support zoning and planning commission actions, or enforcement or variance functions that in New York are assigned to the Department of Buildings or the Board of Standards and Appeals.

The Commission received testimony that the Charter should create the position of a zoning administrator with the power to administratively allow modest residential developments of up to 6 units and up to 35 feet in height conditioned on certain findings.93 In response to testimony, the Commission may consider whether a zoning administrator function can serve a productive and appropriate role that could reduce process costs for certain classes of residential actions and projects that do not require fuller public review in order to facilitate the kinds of projects that do not occur today.

General Changes to ULURP

While most testimony focused on expedited approval procedures as an alternative to ULURP for defined categories of actions or projects, other testimony recommended general changes to ULURP for all actions and projects in order to reduce process costs across the board.

The most common recommendation has been to consolidate the advisory portions of ULURP—that is, Community Board, Borough President, and, when applicable, Borough Board—into a single review period. This suggestion would preserve an advisory role for the Community Board and Borough President, but could save meaningful time. Today, the Community Board review period is generally 60 days and Borough President and Borough Board review add another 30 days. Consolidation could thus reduce the overall review period from 90 days to 60.

The Commission may consider general changes to ULURP that address the process costs that effectively bar more modest zoning changes and create headwinds for the city’s efforts to address the housing shortage and other pressing contemporary problems.

Other Land Use Procedures

The Commission has received testimony encouraging the Commission and its staff to consider excessive process costs associated with other land use procedures, such as approvals for projects on land controlled by Health + Hospitals. The Commission received testimony that projects like Just Home, which would build supportive housing on the H+H Jacobi Campus in the Bronx, have languished before the Council in the absence of definite time limits for Council action. As the Commission heard at its first public hearing:

“The process to get Just Home [a supportive housing project] across the finish line has taken years, and we still have no idea if and when it’s going to get approved. More than two years ago, Bronx CB 11 had a hearing about Just Home where my friends were harassed and faced threats of violence for simply being in favor of the project. More than one year ago, Just Home finally made it to the Council. But the Council has stalled on it because they are not bound to any time constraint." 94

Mindful that many of these processes are structured by state law, the Commission may examine whether changes to the Charter can enable projects like these to get the consideration and ultimate decision—up or down—that they deserve.

Elevating Citywide Needs

In the testimony received by the Commission so far, there is broad consensus that New York City is not building enough housing, that this truer in some neighborhoods than in others, and that the city’s current process for enabling housing growth is a major reason why.

Perhaps the leading complaint heard by the Commission is that the Charter process has come to give too little attention, and too little force, to citywide needs. Rezonings that would add housing are downsized, vetoed, or never proposed because the structure of ULURP gives decisive weight to the views of local councilmembers. The Commission also heard testimony that this parochial, locally focused system likely reinforces economic and racial segregation by precluding housing growth in some areas while concentrating it in others.

Comprehensive Approaches to Planning

As outlined above, one leading set of reform proposals would establish a new comprehensive approach to planning that would, first, include a citywide assessment of how much housing is needed and how it should be distributed and, second, create an alternative public review procedure for projects in line with those plans.

At the heart of these proposals is the belief that the City will most effectively tackle the housing crisis if it considers its housing needs on a citywide basis, rather than through a series of piecemeal projects that tend to be viewed through a hyperlocal lens. The City Council’s recent passage of City of Yes for Housing Opportunity—which authorized significant new housing across the City, including in districts where local members voted against the plan—lends significant support to the view that citywide planning offers a powerful avenue to unlock housing production and overcome otherwise stubborn roadblocks to needed housing.

Speaker Adrienne Adams’ “Fair Housing Framework” legislation—which received unanimous support in the City Council and was signed into law by Mayor Eric Adams—further suggests that there is a broad political consensus in favor of a more comprehensive approach to housing and planning.95 That law, among other things, directs the Administration to assess the total number of housing units, affordable housing units, and other housing units needed across the city, and to propose district-level housing targets for each Community District every five years, with a particular focus on equity and the desire to advance housing opportunities in every community.96

One genre of reform proposed to the Commission would seek to build on the Council’s Fair Housing Framework by creating an enforcement mechanism for communities that fail to meet district-level housing targets.97 Because the Fair Housing Framework is an ordinary local law—which cannot amend the Charter’s land use review procedures—it can only promote disclosure and transparency around patterns of housing development but cannot directly affect those patterns. If a Community District fails to meet a target, nothing about the land use process changes. The New York Housing Conference, Open New York, the Fifth Avenue Committee, Enterprise Community Partners, the Thriving Communities Coalition, the Association for Neighborhood & Housing Development, and others have proposed amending the Charter to create a new, streamlined review procedure for some subset of housing projects that would apply if, and only if, a district failed to meet a target.98 Ultimately, under any such approach, if a Community District meets a housing target in line with the Fair Housing Framework, nothing about the current ULURP process would change.

Any reform to establish mandatory housing targets must answer several critical questions, including: who would set the targets and how; how often targets would be updated; how progress toward targets would be measured; what kind of projects would qualify for streamlined review (including, potentially, affordability requirements or limits on size); and who would decide whether to approve projects in the streamlined review. The Fair Housing Framework enacted by the Council answers many of these questions, but if that framework were given real “teeth” in the Charter, some adjustments might be necessary. In considering such a reform, the Commission may look to models from jurisdictions across the country that impose “Fair Share” housing requirements on local jurisdictions, such as California, Oregon, and New Jersey.99 The Commission may also examine how capital planning processes set out in the Charter may need to change to ensure investments in infrastructure, transportation, and neighborhood amenities are made in concert with new housing.

Others—including Comptroller Brad Lander and Borough President Antonio Reynoso—have proposed that the Charter be amended to require that the City adopt a more ambitious “comprehensive plan” that would touch not only housing but other critical aspects of planning, including economic and workforce development, transportation, sustainability, schools, and access to open space. Other cities, including Seattle, develop comprehensive plans of this kind, frequently pursuant to state law.100 Seattle’s plan does not by itself change land use rules (like allowing new housing on a particular lot) or dictate specific infrastructure investments. Nor is it a hyper-detailed, block by block and lot by lot, assessment of appropriate zoning, transit investments, and so on. Instead, the plan is used to help guide later decision-making over specific land use, infrastructure, and other proposals.

New York City once had a similar comprehensive planning requirement. Both the 1936 and 1961 Charters required the City Planning Commission to adopt a “master plan.”101 In 1969 the Lindsay administration produced one such master plan — the “Plan for New York City.”102 That sweeping five-volume plan touched everything from jobs, to transit, education, housing, industrial growth, open space, and more. But the plan was never adopted and “came to be viewed as a costly failure,” leading to the removal of “master plan” requirements from the Charter in 1975.103 Today, Section 197-a of the Charter gives the City Planning Commission the power to adopt “plans for the development, growth, and improvement of the city” proposed by the Mayor, Borough President, Borough Boards, Community Boards, the City Planning Commission, or the Department of City Planning.104 Likewise, Section 192(f) of the Charter requires the City Planning Commission to prepare, every four years, a “zoning and planning report.” But only one such report has been prepared, in 1993.105 Previous Charter Revision Commissions have considered reintroducing a comprehensive plan requirement but have declined to forward a proposal to voters.106

Comptroller Lander’s proposal would task the City with developing a comprehensive plan, condition the adoption of that plan on approval by the Council, revise the City’s 10-year capital plan requirement to reflect a comprehensive plan, and create a “streamlined and expedited 90-day ULURP clock for rezoning actions that comply with the Comprehensive Plan” that ends with the City Planning Commission.107 Borough President Reynoso, for his part, argues that aligning the City’s capital plan with a comprehensive plan will give assurance to communities that housing growth will be accompanied by investments in infrastructure and replace the need for ad-hoc agreements on individual proposals, which are a mainstay of the current member-centered process.108 Others including the Association for Neighborhood and Housing Development and Pratt Center for Community Development have emphasized the need for comprehensive planning to ensure broad equity goals that expand beyond just housing and to ensure sustained and meaningful community engagement in the development of such a plan.109

Reform along these lines would need to confront several critical issues, including how such a plan would be drafted; what subjects it would address; how it would be reviewed and approved; and what—if anything—would change about public review of actions that align with an approved plan. The Commission may consider whether a lengthy comprehensive planning process, if it does not result in adopted plans or does not trigger an alternative public review procedure for projects in line with the plan, would result in significant additional delay and process costs for proposals to build housing and address other needs, exacerbating existing problems rather than ameliorating them. And the Commission may carefully consider whether burdensome state environmental review requirements would constrain the content, level of detail, and subsequent planning implications of a comprehensive plan, as well as the length of the process to develop a plan, and the potential that litigation challenging such a plan would introduce further delay and uncertainty in the planning process.

The Commission may also consider whether the complexity of New York City, which is an order of magnitude larger than other American cities that have embraced comprehensive planning, may make comprehensive planning difficult, and how such a comprehensive plan would interact with other, more focused, planning requirements in local law, including the above-mentioned Fair Housing Framework and the local law requirement that the City develop an Industrial Development Strategic Plan.110 In doing so, the Commission may look to the City’s own history with master planning, and its decision to abandon its previous master planning requirement in 1975. Reforms in this arena would also require careful consideration of changes to the City’s multiple and overlapping capital planning processes, including its Ten-Year Capital Strategy, which pursuant to Section 215 of the Charter is prepared jointly by the Office of Management and Budget and the Department of City Planning.

Empowering Boroughwide and Citywide Actors

An alternative set of proposals would attempt to give actors with boroughwide and citywide perspectives new power over projects of citywide significance. What animates these proposals is a view that the City’s current land use process wrongly gives determinative weight to the views of individual local members. Empowering officials with boroughwide or citywide perspective, it is argued, will make it more likely that consideration of land use proposals includes appropriate attention to citywide priorities, like addressing the housing crisis.

City history supports the idea that officials that represent broader constituencies are more likely to emphasize citywide needs. As recounted above, data suggests that in era where the Board of Estimate had final say in ULURP, the Board saw and approved more proposals to consider new housing,111 even as that body continued to give significant consideration to advisory votes of Community Boards.112 Strong leadership from Speakers of the City Council—from Speaker Vallone’s dominant approach to land use matters in the 1990s, to Speaker Adams’ forceful efforts to secure the passage of City of Yes for Housing Opportunity113—similarly suggests that Speakers can be a powerful force for ensuring citywide interests trump parochial concerns. Former councilmembers who have ascended to higher office personally report that representing a wider constituency has altered their perspective and given them the opportunity to take a broader view on land use matters.114

In this spirit, the Commission has received a wide range of proposals to empower citywide and boroughwide officials. Borough President Reynoso has suggested replacing Borough Presidents’ advisory vote before the Council with a material role after the Council, to ensure that proposals receive a “borough-wide view on how development should happen” rather than a “very local view.”115 Borough President Gibson has similarly suggested that Borough Presidents should have “more of a final decision and say” in ULURP, given that they possess a “lens that extends beyond a local council district.”116

Along these lines, some have suggested that ULURP’s mayoral veto could be replaced with an appeal to a new three-official body including the Mayor, Council, and the relevant Borough President, with the agreement of two of the three officials needed to override a Council action. Still others have suggested that the Speaker should be given the power to call up actions to the City Council rather than relying on a majority vote of the Council in order to do so.

Taking a different tack, the Citizens Housing & Planning Council has suggested giving the Speaker an appointment to the City Planning Commission, and then allowing the City Planning Commission to override or modify Council land use actions by a supermajority vote.117 It argues that this new City Planning Commission override would newly empower Borough Presidents and the Speaker, as mayoral appointees to the Commission would be insufficient to constitute a supermajority without the agreement of some appointees of Borough Presidents and or the Speaker’s appointee. Similarly, the Citizens Budget Commission would create a new ULURP Appeals Board consisting of the City Planning Commission and the Speaker, which would have the ability to override the City Council upon the assent of 10 of the 14 members.118

Any reform to empower the Speaker, Borough Presidents, or the City Planning Commission will need to consider a number of important issues. ULURP governs review of many non-housing land use issues, and many of these reform proposals would alter how ULURP functions on critical non-housing matters. To focus reform more surgically on addressing the housing crisis, any new measure to empower citywide and boroughwide actors could reasonably be limited to proposals involving housing, or even a limited set of housing proposals, such as projects that meet certain affordability requirements, limits on size, proximity to transit, or labor standards. Likewise, Commission staff is mindful that any procedural change is likely to have unintended knock-on effects—like the emergence of member deference itself after the 1989 revisions—that must be carefully considered.

Any change in this domain should preserve meaningful opportunities for local input. The Commission may take care to ensure that any reform strengthens democratic accountability, namely by securing the power of majorities of city voters to influence land use decision making at the ballot box. Any reforms must also grapple with the reality that today member deference is one of the most important ways that local priorities—channeled through a community’s elected councilmember—shape proposals for development and secure community investments.

Leveraging Public Land

As the city grapples with the ongoing housing shortage and affordability crisis, there is near-universal acknowledgment from elected and other government officials, advocates, practitioners, and members of the public that the City should be leveraging publicly owned, underutilized land to the greatest extent possible. The City exerts far greater control over property it owns than over property it does not, and that power gives the City greater latitude to ensure that land is developed in ways that address the city’s most pressing problems. The Commission has received extensive testimony on this topic and the rules that presently govern City activation of public land, including Charter procedures governing dispositions of City-owned property, as well as acquisitions, administration, and related procedures.

At the time that the 1989 Commission was evaluating the process for disposing of public land, the city had roughly 1 million fewer people and a massive portfolio of in rem properties acquired via abandonment and tax foreclosure in the aftermath of the City’s fiscal crisis and population decline in the 1970s. Compared to today, the City possessed a far larger stock of large and underutilized land appropriate for housing development, especially in low-cost neighborhoods. For decades, and especially during the Koch administration, the City’s affordable housing policy turned on putting these properties back to productive use, typically by selling or leasing them to affordable housing groups, neighborhood nonprofits, and “urban homesteaders” with affordability restrictions and for low- or no-cost.119 (These “HDFCs,” or Housing Development Fund Companies, remain an important pool of affordable housing to this day.) The fruits of those efforts can be seen across the city, from the Nehemiah Homes in East New York and Brownsville, to rows and rows of formerly abandoned buildings on University Avenue in the Bronx that now bustle with activity. Many remain bastions of affordability in a city struggling to adapt to the housing crisis.

Because dispositions are project-specific rather than legislative in nature, the 1989 Charter Commission did not initially propose to subject them to automatic review by City Council. But critics pointed to the City’s largest, vacant properties, and argued that a city disposition of a tract of that size was “the functional equivalent of a zoning change” for poor communities and, as such, should be subject to full ULURP just as rezonings are.120

The Commission acquiesced but attempted to carve out an exception for “dispositions…to companies that have been organized exclusively to develop housing projects for persons of low-income”—that is, HDFCs.121 Under this exception, applications would go to City Council only if a majority of the Council voted to review it. In practice, this exception has been rendered irrelevant by City Council’s broader tendency to call up any application over which it has that authority, meaning that virtually all dispositions now go through full Council review. As a result, today’s procedure, which was intended to capture the largest outliers, instead captures all actions, no matter how small or how urgent. The result is a Charter that requires a multiyear process for dispositions to affordable housing nonprofits, even for projects that meet zoning requirements, or when the City seeks to sell unusable sliver lots to adjacent owners, impeding the City’s ability to leverage public property.

The 1989 Commission’s “one-size-fits-all” approach to ULURP also subjected other actions related to City-owned property to the full ULURP procedure, including acquisitions, part of a move late in that Commission’s process to eliminate gradations and tiers among project types in favor of a simpler approach that the Commission believed stood a better chance of being approved by voters. According to testimony received by the Commission, decades of experience since 1989 indicate that this regime makes many projects involving City property unnecessarily difficult, delaying or rendering infeasible affordable housing projects, new parks, and vital infrastructure (discussed more fully in separate sections below), among other projects.

To that end, and responding to the volume of testimony on this subject, the Commission may carefully explore modifications to the Charter that streamline applications involving City-owned property where appropriate. In particular, the Commission has heard recommendations for a less time- and cost-intensive process for dispositions generally or for dispositions meeting certain criteria, including exempting certain dispositions from an additional public auction process; and reduced procedure for acquisitions meeting certain criteria.

Faster Dispositions

The Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD) handles the large majority of dispositions of City-owned property for housing in New York City under various sources of authority, including Urban Development Action Area Projects (UDAAP), Article XI dispositions under the Private Housing Finance Law, and a few lingering Urban Renewal Projects, all of which are subject to ULURP. Almost all housing facilitated by these dispositions is affordable, and dispositions are typically to Housing Development Fund Companies, organized under state law to provide affordable housing. Because the City generally tries to leverage its property to the greatest extent appropriate, dispositions usually happen in conjunction with other ULURP or ULURP-like actions such as tax exemptions, zoning map changes, special permits, and zoning text amendments to map Mandatory Inclusionary Housing.

After decades of dispositions for affordable housing, the largest sites that can support affordable housing without rezonings and other actions are largely gone. Much of today’s disposition pipeline consists of creative uses of small, medium, or irregular sites. If these dispositions do not include other actions, then they are by definition dispositions pursuant to zoning, that is, dispositions that can only produce development that any other owner would be able to build as-of-right. Yet, the ULURP process designed for evaluation of complex changes in land use is applied to these projects, making it more challenging to use public land for public use than it otherwise would be if it were privately owned.

The Department of Citywide Administrative Services (DCAS) handles dispositions involving residential property as well, though these dispositions tend to be considerably more modest than anything HPD handles. DCAS’s main disposition pipeline is the “SAIL Away” program, which disposes to adjacent property owners City-owned slivers, accessways, and interior lots (hence the “SAIL” acronym) that cannot support independent development. Even though these lots are by definition too small, irregular, or otherwise encumbered to be of any possible use to the City—some slivers are just inches wide—they require the exact same public review process as the dispositions to facilitate Hudson Yards.122

The Commission has received testimony that at least some categories of dispositions involving residential uses should have access to a streamlined process. Several parties recommend a “fast track” for affordable housing dispositions.123 In most instances, dispositions occur to a particular purchaser for a particular project. Under this approach, projects meeting certain affordability criteria could access the streamlined process while other dispositions would remain subject to ULURP. These criteria could be defined in terms of a percentage of affordable housing or by the nature of the purchaser. One approach could revisit the unsuccessful attempt of the 1989 Charter Commission to create a fast track for dispositions to HDFCs, which by definition exist to provide affordable housing. The Commission has received varied testimony on how the process should be modified, with some suggesting that such dispositions do not raise legislative or planning issues that require review by City Council, and others suggesting that narrowing the process to a Council vote best balances efficiency with adequate review. Others have suggested that the Charter should authorize subsequent rulemaking that would detail which types of dispositions require ULURP and which have access to a lesser procedure. The Commission may examine the full range of options.

Some testimony noted that a “fast track” already exists under state law for certain UDAAP projects. While UDAAP dispositions generally require ULURP, “accelerated UDAAP” projects have access to a faster process and go straight to City Council for a vote. These criteria are exceedingly narrow, however—they are generally available only to developments of up to four units or rehabilitation of existing buildings.124 Nonetheless, “accelerated UDAAP” is a potential model that the Commission may examine closely.

The Commission also received recommendations to relieve some dispositions from full ULURP. Any such reform would presumably capture most dispositions under the SAIL Away program, which by definition is available only for lots that, due to size, shape, or other factors, are not capable of being developed independently. This proposal is similar to recommendations described above for zoning map changes, some special permits, and other actions that require ULURP regardless of magnitude. In the case of private applicants, these process costs simply mean that beneficial projects never get off the ground and do not happen. For public actions, like dispositions, the result is expended staff time on processes that do not improve outcomes and increase costs, making affordable housing projects cost more than they otherwise would and reducing the amount that can be produced.

Additional Disposition Process