Another obstacle to housing production and infrastructure projects is the City’s arcane and archaic administration of the City Map. The City Map shows the location and grade of streets, blocks, parks, and other features that define and limit where housing and infrastructure can be built, which agencies have jurisdiction, and what procedures must be followed. The map itself (a collection of thousands of paper maps) and its decentralized method of administration trace back to the pre-consolidation era in the late 19th century, leading to frequent delays for projects that require confirmation of, or updates to, the City Map. Decentralized administration can also pose problems for other aspects of the development process, including the obscure but essential task of assigning unique addresses needed for permitting and other property-identification systems.

According to testimony received by the Commission, these issues add time and money to urgent housing and infrastructure projects and reform to Charter provisions governing the City Map merits examination.1

The City Map is the official street map of the City of New York. It establishes the legally defined locations of street lines, widths, names, and legal grades, as well as the locations of mapped parkland and public places.2 Changing the City Map, or “confirming” the City Map (i.e., establishing clear jurisdiction over mapped areas for purposes of building or reconstructing public or private infrastructure and housing), can be time consuming, costly, and highly complicated.3

New York is an old city whose current boundaries were created by the consolidation of the five boroughs of New York under one government in 1898. A unified City Map of all five boroughs was never adopted, so today the City Map consists of five different sets of maps, one for each borough, totaling over 8,000 individual paper maps. Each borough is divided into separate sets of Section Maps that cover every block. The maps for each borough are accessible in the Borough Topographical Bureaus within each of the five Borough President offices. These maps vary by scale, standard details, and in some cases different topographic “datums,” or elevations that serve as an official reference for measurements involving heights.4

Alterations

The Charter provides the Department of City Planning (DCP) with the authority to maintain the City Map, but the Charter requires the Borough Presidents to maintain a Topographical Bureau, responsible for reviewing and approving any alterations to the City Map.5 Virtually all other land use functions formerly assigned to Borough Presidents have been centralized for over 60 years—since the 1962 Charter—and it has become increasingly difficult to staff Borough President Topographical Bureaus and sustain this function within Borough President Offices over time.6

Stakeholders have reported to Commission staff that diminished capacity within Borough President Topographical Bureaus means that some offices have the capacity to process only three or four City Map changes per year. As a result, routine alterations can take years to get to the starting line. The queue is also unpredictable, since priorities of the Mayor, Borough President, or other officials can skip to the head of the line. Even the Department of Housing Preservation and Development reports that a City Map issue can add six or more months to a project timeline, not counting any associated ULURP.

Borough Presidents themselves play a ministerial but essential role in applications for changes to the City Map, with their signoff needed on the application and again on any approved alteration map. In recent decades, stakeholders have reported that inattention to this minor non-discretionary signature requirement has delayed projects for months or even years.

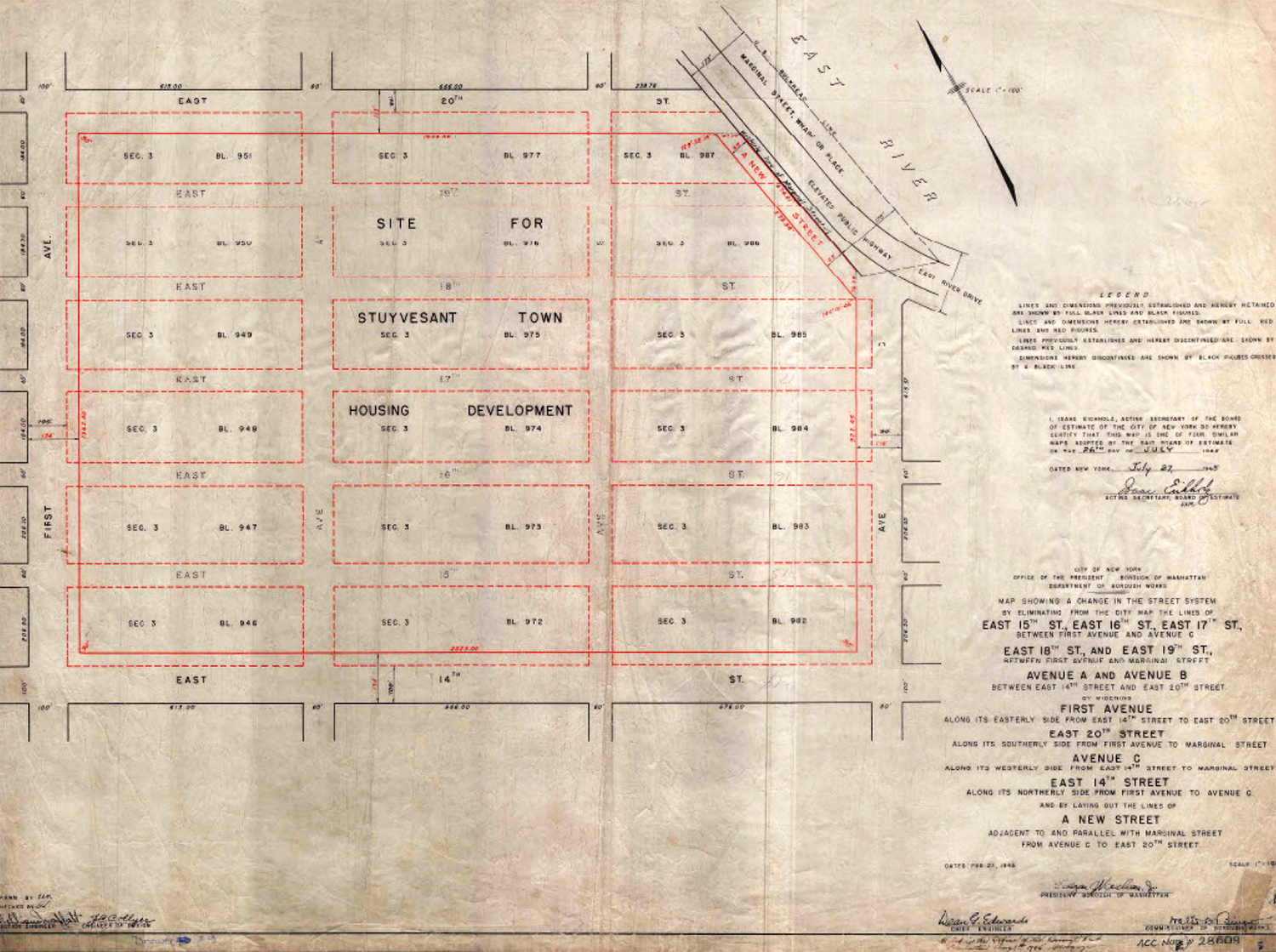

DCP’s online archive of historic Alteration Maps.

Confirmations

The City Map changes over time—as streets close or change, and new streets or parks are added—and Alteration Maps are prepared to illustrate these changes. Together, adopted Section Maps and Alteration Maps constitute the City Map and document the current status of the streets in the city. DCP has created an online archive of historic Alteration Maps, but aspects of the City Map must be confirmed by official documents accessible only from the respective Borough President Topographic Office.

Confirming the location, width, and legal grade of mapped streets is necessary for a wide variety of housing and infrastructure projects. In some districts, permitted density and height depend on whether a street is “wide” or “narrow”—that is, more or less than 75 feet in width on the City Map. The grade of streets establishes the base elevation for allowable building height and determines location for points of access for vehicles and pedestrians. Grade also drives the design of below-grade infrastructure, such as utility lines and subways, which must have a minimum two feet of soil cover to protect them, but not so much that it compromises the structure or limits access. The slope of streets, a product of legal grade, determines the direction, drainage shed area, and sizing of our sanitation and storm sewer system. Street status letters are included in title reports, and address verification letters are often necessary to satisfy access requirements so that DOB can issues permits.

The above gives a partial sense of the universe of potentially affected projects. Given the analog nature of the official City Map and capacity issues in Topographical Bureaus, even projects that merely need to confirm the status of the Section Map for their parcel can face significant delays. In many ways, the process of confirming the status of the City Map via the relevant Section and Alteration Maps underscores the extent to which the system is stuck in the early 1960s. The process has remained largely unchanged since that time.

Address Assignment

The ministerial (that is, non-discretionary) process of tracking the unique addresses of properties and buildings is the backbone of many of our permitting and property information systems. The process of changing property boundaries and identification can cause delays in the construction permitting process when data changes are not efficiently administered.

DCP maintains the Property Address Database System (PADS), GeoServices digital application, and Citywide Street Centerline dataset used by 40 agencies to locate buildings in New York City. The PADS database provides a geographic location for three unique identifiers: Borough, Block and Lot (BBL) number, street address number, and Building Identification Number (BINs). The tools are critical to the administration of construction permitting, property tax assessment, and emergency services.

The property identification data recorded in PADS is generated by multiple sources. Most of these, such as the Digital Tax Map overseen by the Department of Finance, are centrally administered. After a City Map change, however, addresses are assigned by whichever of the five Borough President Topographical Bureaus is responsible for the property.7 Those bureaus vary in their practices, with some allowing email-based address requests and others requiring in-person, paper-based applications (often during brief, irregular windows of time) that are then physically forwarded to DCP. This fragmented process is another source of delay for housing and infrastructure projects.

1945 alteration map approved by the Board of Estimate and Manhattan Borough President noting the streets discontinued and closed for the construction of Stuyvesant Town.

Areas to Explore

The Commission received testimony suggesting that the administration of the City Map and related functions should be centralized at the Department of City Planning.8 The Commission may explore this suggestion, which could make administration of alterations, status confirmations, and address assignments, among other functions, more consistent and efficient than under the current decentralized process. As related above, it has been a challenge for some Borough President Offices to maintain this isolated and technical function that bears little relation to most other responsibilities of the Borough President offices. But these functions are core competencies of the Department of City Planning, which has a deep well of expertise and citywide jurisdiction. The Commission may also explore whether an amendment to the Charter would facilitate the digitization of the City Map, an advance that could revolutionize aspects of City Map administration that today can take months or years but have the potential to happen almost instantly in the future.

References

1. Charter §§ 197-c, 198, 199.

2. Ad. Code § 25-102

3. Department of City Planning, “Changes to the City Map Application Process and Standards Guide – Version 6.0,” Jan. 2018, at 8, 19.

4. Despite some attempts to standardize datums under certain circumstances (e.g., Local Law No. 96 of 2013) New York City still uses many datums, which determine elevation. See: Department of Public Works, “Datum Chart,” Jan. 1949.

5. Charter §§ 82(3), 198.

6. This is not a new issue. See Department of City Planning, Changes to the City Map, Jan. 2018, at 23.

Prior to the charter revision of 196[1], many city functions were decentralized, performed by line bureaus under the Borough Presidents. These included the Department of Buildings, the Department of Sanitation, the Department of Highways, the DEP – Bureau of Sewers, the Department of Parks and Recreation as well as a bureau of topography, all under a borough engineer. The 196[1] City Charter revision centralized most of these functions into line agencies under the Mayor, thereby vastly reducing the power and prestige of the Borough Presidents.

Only the topographical bureaus, which had been important service bureaus serving the engineering needs of the other bureaus in the Borough Presidents' offices, remained under the Borough Presidents. As the power of the Borough Presidents waned, their perceived need for the topographical bureaus also waned and consequently their interest in supporting the somewhat arcane functions of the topographical bureaus also waned. Over the last several decades, staffing has been radically reduced; junior staff has not been trained to take over and sustain the functions; and professional staff has not been replaced. As senior staff retires, the functions will largely disappear and the institutional memory necessary to revive them will be lost.

7. Ad. Code § 3-506.

8. Elijah Hutchinson, Executive Director of the Mayor’s Office of Climate and Environmental Justice, Staten Island Hearing (Apr. 23, 2025) (written testimony).